A garden, a city, a home, and a judgment

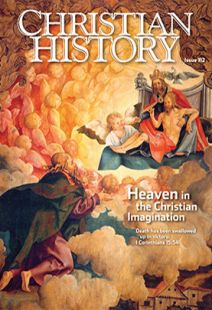

NOWADAYS, TALK OF HEAVEN often brings to mind images of golden gates and smiling cherubim reclining on puffy white clouds. Perhaps the chubby cherubim pluck some innocuous tune on their harps, or there’s a Muzak version of Eric Clapton’s “Tears in Heaven” permeating the airwaves. But such images and songs depart significantly from historic Christian pictures of heaven in music and art.

Artistically, much church architecture was originally intended to speak of heaven. Adapted from the design of the Old Testament Jewish Temple, Christian churches were traditionally divided into three distinct spaces. The narthex, or entry, represented the world. The nave, where the congregation stood or sat, represented the whole church or the kingdom of God. And the sanctuary containing the altar (akin to the Jewish Holy of Holies) symbolized heaven. Gradual procession into the church building and to the altar for Communion paralleled the believer’s spiritual journey, and liturgy was understood as sacred time when believers worshiped alongside the heavenly host. Images of angels and saints mixed with memorial plaques and physical tombs of deceased church members, adding to the effect.

Not only architecture, but art itself, spoke of heaven: often picturing major biblical episodes in which heaven is momentarily revealed, such as the baptism of Christ, his Transfiguration, his Ascension, and the visions of prophets.

Heavenly garden

Because the biblical story of humanity’s origins takes place in a garden, many Christians have historically imagined heaven too as an idyllic garden, restoring humanity to before the Fall. The very word “paradise” came to the English language from the Persian word for “enclosed garden or park.”

The Genesis account of Creation describes Adam and Eve’s environment as full of beautiful vegetation and delicious food (except that pesky Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil). A river of life flowed through it (just like the one that would reappear in Rev. 22), and humans and animals lived there in harmony. Throughout the Bible, gardens appear as places where plants flourish, where people hold feasts and drink wine, and even where bodies are buried. The Song of Songs, long read in the Christian tradition as an allegory for the believer’s relationship with Christ, uses garden imagery to great effect (“A garden locked is my sister, my bride, a spring locked, a fountain sealed”). Artists and writers also applied this image of the enclosed garden to the Virgin Mary.

On the facing page, we see an early fifteenth-century painting by an unknown Germanic artist that draws together these rich layers of meaning—symbols of heaven, of Mary’s virginity, and of Christ’s Passion. In a garden enclosed by walls, Mary, draped in her customary blue cloak, daintily turns the pages of a book. Martyrs and angels surround her including fourth-century virgin martyrs Dorothy and Barbara. Barbara draws water from a well, evoking the fountain of life (Ps. 36:9) and the living waters mentioned throughout the Bible.

Cecilia, a second-century virgin martyr and the patron saint of music, sits on the ground, assisting the Christ-child as he plucks the strings of a psaltery (harp). In the bottom right are the archangel Michael, saintly King Oswald of Northumbria, and third-century martyr St. George. George’s defeated dragon refers to a legend of him slaying a crocodile, symbolizing Christian victory over paganism. The presence of the five martyrs recalls the martyrs crying for justice in Revelation 6.

Meanwhile, Mary sits by a bowl of apples—referring not only to the fruit of Eden, but also, when taken with the nearby cup, to the Eucharist. Around her are several goldfinches, long associated with Christ’s Passion because they eat thorns, and a cherry tree—which, due to its legendary reputation as being in the Garden of Eden, indicates paradise.

Paving Paradise

The Christian understanding of heaven as a city draws primarily on Revelation’s description of the heavenly Jerusalem (Rev. 21; see also Heb. 11–12). It has long been a popular metaphor, beginning with Augustine’s City of God, that pits the heavenly city against the worldly city in response to the fall of the Roman Empire.

Another example comes from Beatus of Liébana’s Commentary on the Apocalypse. A monk at the monastery of St. Martin at Liébana in Spain, Beatus (d. 798) was relatively well educated, may have been an abbot, and is credited with several liturgical hymns. He is best known for his Commentary, a compilation of patristic sources (including Ambrose, Augustine, and Gregory the Great). Beatus intentionally structured his book to provide story, picture, and explanation for each passage, hoping that texts and images would work together to aid the reader in meditating on Revelation and achieving a mystical vision of God. Beatus’s Commentary continued to be popular well after his death, widely copied and circulated in at least 30 different manuscripts into the twelfth century.

At first glance, the painting accompanying Revelation 21:15–17 in an eleventh-century copy of the Commentary looks like a board game (see p. 17). In fact, it shows the measuring of the New Jerusalem—that foursquare heavenly city of equal height, width, and length. In contrast to the chaos and violence of earthly cities, images like this emphasize the order of the heavenly city through symmetry and biblical numbers (such as seven, nine, and twelve). Within the arcades of the city walls stand the 12 apostles, looking inward to the center. There the Lamb of God holds a cross—flanked by an angel with a measuring rod to the left and the Apostle John to the right.

Has Waldo gone to heaven?

Some images of heaven focus on the heavenly inhabitants themselves and are often referred to as “all saints” images (commemorating All Saints Day, November 1 in the Western church and the first Sunday after Pentecost in the Eastern). Depicting all the inhabitants of heaven of course proved impossible, but artists hinted at the divine multitude by tightly packing their compositions with haloed figures: a celestial Where’s Waldo, a who’s who of the afterlife.

In Fiesole, Italy, is one such piece: the predella (platform) panels of the Fiesole Altarpiece by Fra Angelico (c. 1394–1455), a Dominican friar. Late medieval altarpieces often have many large panels, opening to display several different images such as the Annunciation, Crucifixion, or Resurrection. In the center panel of this predella (see below), the resurrected Christ stands in glory, with a cross-inscribed halo and wounds on his hands and side—surrounded by five rows of densely packed angels, most of whom play instruments or raise their hands in prayerful worship.

The panel to the left pictures the Virgin Mary, the apostles, and the evangelists. To the left of Mary, Peter holds the keys to heaven in one hand and a book in the other. Several other saints can be identified by clothing or other attributes. The panel to the right of Christ shows three rows of prophets, saints, and martyrs, including David and John the Baptist.

This motif emphasized the communal aspect of heaven—imagining it not as a place, but as a spiritual community transcending time and space, where believers can look forward to being reunited not only with family and friends but also with great spiritual leaders who had paved the way. Standing before an image like this and picking out the saints you knew resembles finding friends or family members in a group photo—but playing this visual “game” encouraged viewers to imagine themselves among the saints, worshiping Christ.

Starry starry night

Images of heaven as a starry night sky came from the tendency to focus “heavenward” when praying and worshiping. The domed ceilings of many Eastern Orthodox churches are still painted as dark blue, star-filled skies, often with Christ the Pantokrator (Ruler of the Universe) at the center, to remind worshipers of Christ’s reign over heaven and earth.

One early “starry sky” appears in a mosaic of the Transfiguration at Sant’Apollinare-in-Classe, a sixth-century church in Ravenna, Italy (shown above). At the mosaic’s center stands a golden bejeweled cross, floating within a starry, dark blue sky and framed by a large medallion. The cross bears a small bust of Christ at its center flanked by text celebrating his lordship.

Atop the surrounding mosaic is a field of solid gold tiles—gold being associated with heaven or spiritual space. Moses and Elijah appear, and reaching down from heaven, the hand of God the Father emerges from the clouds directly above the cross. The bottom half depicts a lush green pasture populated by trees and sheep. St. Apollinaris, first bishop of Ravenna, after whom the church is named, stands below the cross with arms raised in prayer, flanked by 12 sheep, symbolic of the apostles. Peter, James, and John become three sheep gazing up at the transfigured Christ on the golden cross.

“Come, angel band”

Musical conceptions of heaven in Christian tradition have been just as diverse as artistic ones. In contrast to the mute impotence of Satan in hell (at least as vividly imagined by Dante), heaven rings with robust polyphonic praise of God. The Psalms, Isaiah, and Jeremiah all describe the heavens as quite literally singing. In Revelation, John envisions heaven as a place of unceasing song; the four living creatures worship around the throne of God, proclaiming, “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God Almighty, who was and is and is to come!” Isaiah’s “Holy, Holy, Holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!” has been sung in church liturgies since at least the fifth century.

Many hymns and spirituals anticipate the joys of heaven (see “Singing our way home,” pp. 37–39). The early nineteenth-century American folk song “Wayfaring Stranger” evokes a great sense of longing and anticipation of heaven, juxtaposing the struggles of the world with the relief of heaven. The world is a place of exile, of difficult wandering and woe, of “dark clouds”; in contrast, heaven is described as a “bright land” with “no sickness, toil nor danger” where the believer will be reunited with deceased loved ones.

Invoking the pastoral language of the Psalms, the song longs for “golden fields” in heaven. Its refrain, “I’m just a-going over Jordan; I’m just a-going over home,” references the epic longing of the Israelites for the Promised Land, entered by crossing the Jordan River. “Wayfaring Stranger” has been sung in churches for more than a century and recorded by dozens of famous musicians, including Burl Ives, Johnny Cash, and Jack White.

Another nineteenth-century hymn, “Angel Band,” speaks from the perspective of a believer at death’s door: “My latest sun is sinking fast, my race is nearly run; / My strongest trials now are past, my triumph is begun.” The refrain beckons the heavenly host to accompany the singer to heaven: “Oh, come, angel band, come and around me stand; / Oh, bear me away on your snowy wings to my eternal home.” The hymn also imagines sounds heard while passing into the afterlife: “I hear the waves on Jordan’s banks, the crossing must be near. . . .I’ve almost reached my heav’nly home, my spirit loudly sings; / Thy holy ones, behold, they come! I hear the noise of wings.”

And the African American spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” like many spirituals, not only describes the soul’s journey to heaven, but also references the freedom accessed through the Underground Railroad: “I looked over Jordan, and what did I see coming for to carry me home? / A band of angels coming after me, coming for to carry me home.” Heaven as home has been a powerful metaphor for freedom in this life, as well as the next.

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

Quite possibly one of the most recognizable pieces of Christian music is the “Hallelujah” chorus from Handel’s Messiah. George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), born in Germany but an immigrant to England, composed Messiah in 1741—in just 24 days. Originally intended for secular settings (its first performance was a charity concert at the Great Music Hall in Dublin), it has graced sacred contexts as well through the years.

Charles Jennens prepared a libretto for Messiah that compiles and excerpts texts from the Bible into three parts. The first anticipates the Incarnation in the prophecies of Isaiah, Malachi, and Zechariah, ending with the annunciation of Christ’s birth to the shepherds and a brief meditation on his power to heal and redeem. The second describes Christ’s Passion, death, and Resurrection in texts from Isaiah, Psalms, Lamentations, John, Romans, and Hebrews. The final part, taken from Job, 1 Corinthians, Romans, and Revelation, celebrates the judgment and resurrection of the dead and Christ’s glorification in heaven.

Part two’s final chorus, the one we all know, takes its text from Revelation 19:6; 11:15, and 19:16 (the seventh trumpet and the marriage supper of the Lamb):

Hallelujah: for the Lord God Omnipotent reigneth. The kingdom of this world is become the kingdom of our Lord, and of His Christ; and He shall reign for ever and ever. King of Kings and Lord of Lords. Hallelujah!

The chorus became further associated with heaven through the apocryphal story, one of many spread by nineteenth-century Handel enthusiasts, that the composer was found weeping while writing it and confessing, “I did think I did see all Heaven and the great God Himself.”

Handel was indeed a sincere Christian but more practical than mystical. A better-attested story tells of the first performance of Messiah in London in 1743, attended by King George II (who reportedly began the tradition of standing during the “Hallelujah” chorus). A few days later, Handel visited Lord Kinnoull, who complimented him on the “noble entertainment” presented, to which Handel is said to have replied, “My Lord, I should be sorry if I only entertained them; I wished to make them better.”

Judgment day

Since the Middle Ages, the text of the Requiem Mass for the Dead has commemorated the transition of countless souls from this life to the next. The Latin text, developed throughout the high and late Middle Ages, adds to the prayers of an ordinary Mass further pleas for God to grant eternal rest to the departed and mercy to the living—and describes the day of judgment in vivid detail. The text has been set to music in many variations, from traditional plainsong for the liturgy to elaborate versions for concert performance—including famous requiems by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) and Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901).

Mozart began composing his (rather melancholy) Requiem in D Minor in 1791 and died that December before its completion. In contrast to Mozart’s,Verdi’s Requiem (1874) is long and loud. In a performance at the Royal Albert Hall in London, Verdi directed it with a choir of more than 1,000 voices accompanied by a 140-piece orchestra. It was wildly popular with music-loving audiences, though some churchgoers disapproved of Verdi because of his rumored agnosticism.

In 1944 a group of imprisoned Jewish musicians at the Czech concentration camp of Terezín gave a poignant performance of this piece. Sung with just a single piano before their Nazi captors and the International Red Cross, Verdi’s Requiem took on new meaning. Through the Catholic Mass, set to music by the possibly agnostic Verdi, the Jewish inmates were able to express their condemnation of the Nazis and their desire for justice:

The day of wrath, that day will dissolve the world in ashes

On which shall rise from the ashes

The guilty man, to be judged.. . .

Deliver me, O Lord, from eternal death on that awful day,

When the heavens and the earth shall be moved:

When you will come to judge the world by fire.

The Requiem also describes the experience of those spared judgment, praying, “Grant them eternal rest, O Lord, and may perpetual light shine upon them with your saints forever; for you are merciful.”

This small handful of examples demonstrates something of the incredible breadth and depth of Christian conceptions of heaven expressed in music and art. While the glory of God’s eternal presence is impossible to fathom, let alone describe, it has nonetheless captured the Christian imagination and inspired artists and musicians for generations. CH

By Jennifer C. Awes Freeman

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #112 in 2014]

Jennifer C. Awes Freeman is a doctoral candidate in religion at Vanderbilt University, with a specialty in medieval art and theology, and an image researcher for Christian History.Next articles

New heaven, new earth

The tension between heaven above and new creation to come throughout church history

John StackhouseAnother stop on the glory train?

Christians have wrestled for years—sometimes with each other—over whether there might be a “precursor” to heaven

Jerry L. WallsTill we reach the golden strand

Pilgrim’s Progress gave many generations of Christians a way to understand their journey to heaven

Edwin Woodruff TaitHeaven Lost and Heaven Found

Ever since the Enlightenment, some thinkers have tried to “think away” heaven, but it is still going strong

Jeffrey Burton RussellSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate