Doing “more beyond”

IT ALL BEGAN with a fall into a well. At the age of two-and-a-half, Jennie Fowler Willing (1834–1916) tumbled into a well on her family’s Illinois farm property, struck her head against the side, and sustained severe nerve damage. That injury spurred on chronic health problems that eventually affected her ability to attend school after age nine. For years, she yearned for an education. Finally, at age 28, she asked God to help her get an education so she might do more to serve God and the Methodist Church.

Surrendering to Jesus

Willing (she had married at 19) then dedicated herself to a self-education method of study for 15 minutes a day, because her eyes were too weak to do more. She set a rule that if she missed one day of study, she had to make it up as soon as possible. Even at 15 minutes a day, her method was astonishingly successful. She even taught herself German, was hired by a local school as a teacher, then by Illinois Wesleyan University as professor of English language and literature. She also authored 200 articles and 17 books. Her personal motto, plus ultra—”more beyond”—epitomized everything Willing dedicated herself to accomplish.

Willing, a lifelong Methodist, experienced a religious conversion in her youth during an evangelistic service held in her town, but she wrote more often about her experience of sanctification. Like her dedication to self-education, it occurred at the age of 28.

“I shall never forget the hour when I made that surrender,” she wrote. “One afternoon when the Holy Spirit sent His light into the depths of my soul, I discovered, hidden away, like the wedge of gold in Achan’s tent, a determination to work, and study, and make something of myself. . . . When I saw that, I was enabled to say, ‘I give it all up. Henceforth for me, only thy will, and thy work.’ The pain of the surrender was so severe that a knife seemed to pierce my heart, and the tears leaped from my eyes.”

From that time on, she devoted all of her work to God’s service—primarily through the Methodist Church. Like many middle-class Methodist women in the late nineteenth century, Willing chose mission, temperance, and evangelism as the avenues of her tireless activity. In all three, she resembled many other gifted women of her generation who rose to lay leadership positions though ordination was denied them.

Willing served as an officer in both the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society (WFMS) and the Woman’s Home Missionary Society (WHMS) of the Methodist Episcopal Church. From 1886 to 1890, as secretary of the Bureau for Spanish Work of the WHMS, she oversaw its efforts in New Mexico and Arizona.

Underlying her work in mission was her personal belief that every woman—single or married, childless or a mother—is a missionary. She exhorted women to be active in mission work for God, beginning at home: “Let the home, where she does her best work, have her strongest thought, her main strength, her most devout prayer.” She chastised women who allowed laziness or vanity to deter them from working on behalf of mission.

In particular, she named women who, in her opinion, wasted money on dressing their dogs in “satins, ermine and jewels,” or who wasted their time on “queer bits of fancy work [embroidery]” or “neighborhood tangles that yield only a harvest of gossip and ill-feeling.” Instead, she believed that as a missionary, every woman is obligated to devote herself to be loyal to God to the “heart’s core.”

Committed to the temperance movement as a second area of activity, Willing delivered a stirring speech in 1874 in conjunction with meetings and marches of the “Woman’s Crusade” to support a ban on liquor. The speech led to the formation of a national temperance organization, which she then chaired for a year. Out of it came the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), which grew so rapidly that it became the largest women’s organization in the United States by the end of the century. (Read more about famous WCTU president Frances Willard in “Preachers, fighters, and crusaders,” pp. 35–38). Willing served as vice president of the WCTU and edited its first periodical. Her loyalty to the WCTU lasted throughout her life. When she died at the age of 82, she was president of the New York City unit and organizer for New York state’s WCTU.

Preaching Jesus

The WCTU provided a platform for Willing’s third area of ministry—evangelism. Thousands of women, like Willing, enlisted as WCTU evangelists to preach Jesus Christ and temperance. In one year alone (1896), WCTU evangelists around the country held 75,000 evangelistic meetings, 10,000 religious visits, 6,000 church services, and 3,000 Bible readings; they distributed 4,000,000 pages of temperance literature and prompted 6,000 conversions. Willing served for several years as secretary of the WCTU’s Department of Evangelistic Institutes and Training.

There Willing also continued her calling as an educator, founding the New York Evangelistic Training School in New York City in 1895 after the death of her husband. (They had moved to NYC in 1889.) Her school provided a two-part curriculum in Bible study and practical work to train men and women to be urban evangelists. Located in the heart of New York City at Thirty-second Street near Tenth Avenue, the school stood near the homes and jobs of several thousand factory girls and many young working men who needed, in Willing’s opinion, to hear the Gospel message where they worked and lived.

Students at the school were required, as their practical work component, to give an hour every day to religious visitation in the neighborhood, assist in the school’s evening chapel service, teach Sunday School, give Bible readings, and preach sermons.

In these settings students gained hands-on experience in evangelism and urban mission. Willing also provided evangelistic training in the evening lectures she gave at the school, which were collected in the book How to Win Souls.

In the book’s introduction, Methodist bishop Willard Mallalieu described glowingly its potential to awaken the church to evangelistic work: “If the seventy thousand, more or less, Protestant clergymen in the United States, and as many more Christian men, and as many more Christian women would read this book, catch its spirit, follow its suggestions, and work out, in daily life, its soul winning methods, this whole land of ours would speedily become the prepared inheritance of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

Partners for Jesus

Willing was also a Methodist preacher. In 1853 she had married William Cossgrove (1829–1894), a Methodist minister who was eager to partner with her in ministry. They resided most of their married life in Illinois, where William pastored and Jennie taught at Illinois Wesleyan University and led her mission and temperance organizations. They had no children. Their marriage exemplified a partnership of equals with each supporting the other’s ministry. William, a presiding elder in a local Methodist district, issued Jennie a license to preach in 1873, and she, in turn, served a small church in his district though denied ordination.

In a letter to Jennie, William wrote of his commitment to her ministry, poking fun at the double standard that accepted a man’s prolonged absence from home, but not a woman’s:

We men are a selfish lot. Everyone [sic] of us will avail himself of the help in evangelistic or temperance work that some other man’s wife can give, but it is quite another thing when it comes to having our comfort interfered with. . . . Everybody pities me because you leave me alone so much. I don’t know whether they think I’m too delicate, or that I can’t be trusted to stay alone. If I were a bishop, or a brakeman on a freight-train, or anybody between the two, I might leave you months at a time, and nobody would make a fuss about it.

(Jennie’s brother, Charles Fowler, was in fact a bishop; see “Preachers, fighters, and crusaders,” pp. 35–38.)

Jennie Fowler Willing embodied the best of the Methodist spirit. She personified the Wesleyan way of salvation rooted in an overarching experience of grace, beginning with God’s first stirrings in the soul through prevenient grace to justifying grace at her conversion and sanctifying grace at her sanctification. She exemplified the Wesleyan commitment to a disciplined and methodical life that enabled her—day by painful day—to achieve a high level of education, despite her limitations.

She also embodied the Wesleyan promise of sober living with her dedication to temperance. She lived the Wesleyan commitment to evangelism, especially of the poor and dispossessed, in New York City’s factories and tenements. Finally, she represented the Wesleyan encouragement of women in ministry as she preached in churches, camp meetings, WCTU gatherings, and on the streets of America’s towns and cities. She wrote in Diamond Dust (1881), “’There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female, for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.’ [Gal. 3:28] When the Christian Church cuts down through the gloss and prejudice to the core of the meaning of that utterance we may look for the millennium.” CH

By Priscilla Pope-Levison

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #114 in 2015]

Priscilla Pope-Levison is professor of theology at Seattle Pacific University and author of Building the Old Time Religion: Women Evangelists in the Progressive Era and Turn the Pulpit Loose: Two Centuries of American Women Evangelists.Next articles

Preachers, fighters, and crusaders

Here are the stories of some other Methodists who helped settle—and then transform—a continent

Gary Panetta and Kenneth Cain KinghornThe patriarch broods over his family’s future

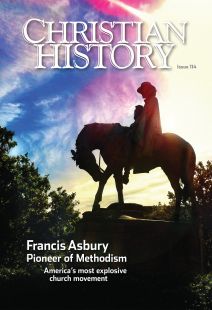

Asbury warned Methodists against settling down like other churches

Francis AsburyThe continent was their parish

Christian History talked with historian Russell Richey about who Methodists have been and how Asbury made them that way

Russell RicheyFrancis Asbury: Recommended resources

Where should you go to understand Methodists? Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate