The man behind the empire

CHARLEMAGNE WAS TALL, handsome, and slightly overweight. He resisted the suggestion of his doctors that it might be better for his health if he ate less roast meat. He enjoyed hunting and riding. Bathing in the warm natural spa baths at Aachen was a special pleasure, which he shared in the Roman way with his entire entourage—and sometimes all his servants—until there might be 100 of them in the baths. He seems to have liked to win swimming races, and usually did.

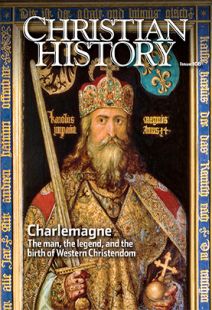

He may have loved Roman baths, but he dressed like a Frank, in a shirt and trousers of linen with a tunic and a blue cloak, covered in winter with an outer garment of sable and otter fur. His sword was always at his side. Dressing was a social business. While strapping on his sandals, he would receive friends and supplicants and often determine a point of law, all while giving the servants orders for the day. He was good-humored and sociable—so sociable that his eagerness to entertain foreign visitors became expensive.

We know these things because one of his courtiers, Einhard, wrote his life story in 814, soon after Charlemagne’s death. Einhard had watched the great man closely and knew him well. “I realized,” he wrote, “that no one could describe better than me events in which I was involved and of which I was an eye-witness. I took careful notes at the time.”

Einhard’s own history illustrates the opportunities for social mobility in Charlemagne’s age. Einhard had a classical education at the monastic school at Fulda (in modern central Germany). His parents sent him there, not to make him a monk, but to give him a good start in life. Recognizing Einhard’s promise, the abbot of Fulda sent him off to be a civil servant at the court of Charlemagne—at that point merely the ruler of the Franks, though a wealthy and powerful one.

Einhard wrote a biography with a message. He had read the Lives of the Caesars by Suetonius, a biography of the Roman Empire’s earliest rulers, and it was Einhard who helped create the legend that as a ruler Charlemagne was the “greatest of his time.”

To the modern reader the story Einhard told seems contradictory. Here was a confessing, committed Christian ruler. He built a great church to the glory of God at Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle), ornate with gold, silver, and fine marble brought from Ravenna in Italy. He provided ceremonial vestments for everyone, from priests to doorkeepers. He gave generously to those in need at home and also to those abroad—in Egypt and Syria; Carthage, Alexandria, and Jerusalem. Yet most of his life was spent in expansive warfare, conquering and subduing his rivals and ruthlessly expanding the territory he controlled until he had made himself an empire with pretensions to rival Rome at its peak. The spoils of war allowed for his extravagant generosity to the needy.

Europe was no longer what it had been several centuries before under the Romans: governed by a centralized legal system and by educated provincial administrators, in an empire that stretched from the British Isles to the Middle East. Migrations from the east had first weakened and then wrecked those sophisticated governmental arrangements. Charlemagne and his Franks were part of this migration.

A once unified empire had become tribal, ruled by rival monarchs grabbing power and lands from one another in endless fighting, and increasingly multilingual as Latin faded from general use as a universal language. Europe was of very mixed religious beliefs—pagan, Arian Christian, and Catholic Christian. And the new religion of Islam, founded by the prophet Mohammed (c. 570–632) was making inroads through an active program of invasion. Muslims would hold North Africa and much of Spain until the late Middle Ages. When Charlemagne came to the throne in the late eighth century, they were dangerously close to capturing northern Europe and Italy.

Charlemagne the empire-builder

Where did Charlemagne fit in all this? Einhard began by explaining how the Franks, originally from the Rhine River valley and roughly the people who became the modern French, had previously chosen their rulers. The founder of their line of kings, Merovech, was a semilegendary figure; his dynasty, vibrant at first, came to an end in the mid-eighth century after petering out into incompetence.

The last of the Merovingians sat on their thrones wearing their titles, and the long hair and beards that were a sign of royal birth, but the real power lay with the Mayors of the Palace. The mayors tended to represent the interests of factions of nobles rather than to act as servants to the king. The king might receive foreign ambassadors, but in reality he was merely speaking for the Mayors of the Palace, who in turn represented the wealthy nobles.

This figurehead monarchy could not survive in a violently changing Europe. Eventually the mayors became the kings. Charlemagne’s father, Pepin the Short, deposed the Merovingians and became king of the Franks from 752 to 768. Pepin had a monastic-school education at St. Denis near Paris and experience serving as Mayor of the Palace.

Pepin divided the Frankish kingdom between Charlemagne and Charlemagne’s brother Carloman (who died in 771). Charlemagne later gave power to several sons too. It was a useful device for discouraging attempts to seize power from a parent, and it helped to pin down conquered territories with a visible royal presence who represented the ultimate monarch. Einhard reported that Carloman was jealous and resentful, though Charlemagne showed exemplary patience and never retaliated.

Tireless fighter

Einhard put warfare first in his story, detailing Charlemagne’s campaigns to conquer territories (often baptizing conquered peoples in the process; see next page). Anyone traveling around continental Europe today is struck by the immense distances Charlemagne’s empire eventually covered, as well as his success in fighting on so many fronts at once with the small armies of the time and against tribes that were likely to bounce back after initial defeats. In many ways, his battles transformed a powerful kingdom into an even more powerful empire.

Some wars Charlemagne inherited. First he fought in Aquitaine, to his south and west, following his grandfather and father. Then he was persuaded to fight against the Lombards (modern north Italy). This too was his father’s war. At the beginning of the fifth century, the northern Italian city of Ravenna had become capital of the western Roman Empire, but the Lombards then invaded north Italy. Charlemagne’s father arrived in Italy in 756 to drive the Lombards out and hand over the conquered lands to the pope.

This was an action of immense importance. It shifted the balance of power. It also gave rise to the papal claim that Pepin had renewed a gift known as the Donation of Constantine, under which the balance of power between church and state was settled in favor of church supremacy. This document, a bold forgery, claimed that the first Christian emperor, Constantine (reigned 306–337), had handed over control of temporal affairs to Pope Sylvester I (d. 335). The Donation of Constantine was an eighth-century invention, but it would be centuries until scholar Lorenzo Valla (1407–1457) exposed the fraud.

Charlemagne continued his father’s battle. Einhard withheld the details of the Frankish army’s struggles to cross over the Alps. Charlemagne helped to consolidate and recapture for the Romans all that they had lost to the Lombards. Once he felt he had Italy under his control, he sent another Pepin, one of his sons, to rule it.

Next Charlemagne renewed a long-standing war against the Saxons. These Germanic tribes held territories stretching from the North Sea to the Rhine. Einhard said this war went on for over 30 years, with the defeated Saxons repeatedly submitting, promising to obey Charlemagne as their ruler, even abandoning their pagan religion for Christianity, then recovering confidence and returning to battle.

Charlemagne fought in person in only two battles, though the cost in death and injury to his loyal Frankish soldiery was high. He eventually began to succeed by capturing groups of Saxon tribesmen and their families and relocating them in Gaul and Flanders.

Charlemagne also tackled the Spanish. On the way home from victory in Spain, bandits ambushed his Frankish army, capturing the baggage train and killing the men in charge. Einhard even gave the names of the dead. Little did either Charlemagne or Einhard know that one day this ambush would be told as Charlemagne’s most powerful legend of victory (see “The thousand lives of Charlemagne,” p. 39).

Charlemagne also conquered the “Britons” (Bretons), living in modern Brittany. Then followed (787–88) a brief but successful war with the Bavarians; then war against the Slavs on the northern shores of Europe facing the Baltic Sea. The Huns, an important enemy, were so thoroughly eradicated, Einhard wrote, that all their nobility perished and all their treasures (plundered from other tribes so not really theirs, he suggested) carried off. Charlemagne fought the last of his wars against the Danes, who were arriving in pirate ships to steal from people on the other side of the Baltic.

This was quite a program of warfare. This energetic conquest—defense, Einhard called it—vastly enlarged the realm of the Franks and made it plausible for them to regard themselves as an empire, even before Charlemagne acquired his imperial title.

Charlemagne’s standing in the world enabled him to exchange courtesies with Muslim caliph Haroun-al-Rashid, who ruled territory from North Africa to India. His delegation was received with courtesy, and Haroun declared that the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem should be considered Charlemagne’s. He even sent Charlemagne an elephant (see “Did you know?,” inside front cover). Relations with the Greek-speaking eastern empire, the last survival of ancient Rome, remained sensitive (see “Sacred kingship,” pp. 16–18). Charlemagne needed to ensure that his adoption of the title of emperor would not cause dangerous offense. So he made a treaty with the Byzantines to try to protect against adverse future consequences.

Learning to spin and read

Charlemagne has the credit for promoting a Carolingian Renaissance (see “For the love of learning,” pp. 24–29), although even before he came to the throne, the intellectual life of Europe was mainly in the hands of monastic and cathedral schools, with the exception of a few schools that seem to have survived from the Roman period in some of the Italian cities.

Charlemagne’s own birth and childhood are a blank. Einhard said he had no information and no one could tell him anything. But it seems certain that the future ruler grew up a Christian. Einhard claimed that Charlemagne became interested in education when he had so many children to educate, but he described a child-rearing policy that does not seem very intellectual.

The king ordered that the boys should learn to ride and to handle arms. The girls were to learn to spin, sew, and practice arts that would develop virtuous habits, not sit about in idleness that would encourage bad behavior. He spent time with his children, keeping them with him on his travels. The boys rode with him, and the girls traveled in special carriages behind with servants to protect them.

Charlemagne had a flexible view of marriage, with numerous mistresses, but he had only one legal wife at any time. He had many children, including famous bastard son Pepin the Hunchback, the result of one long-term relationship. The first of his series of wives, a daughter of the Lombard king, was his mother’s recommendation. He divorced her after a year and immediately married Hildegard, the daughter of an influential Teutonic noble. She bore him seven or eight children including another Pepin; immediately after her death in 783, he married Fastrada, daughter of an influential Frankish count. His last wife was yet another daughter of an influential noble.

Not all his family were happy and loyal. Pepin the Hunchback was caught jealously plotting with ambitious Franks to seize the throne for himself. He was sent to a monastery where he could do penance, with his long royal hair cut short.

Charlemagne never learned to write. This was not for want of trying; he kept a wax tablet under his pillow to practice. Nevertheless his intellectual interests were strong. Charlemagne enjoyed being read to while he ate (and he ate a great deal) and listening to music. He liked history; Einhard mentioned in particular how he enjoyed Augustine’s The City of God, with its high sense of the providential purpose of God for people and nations and its stories of the ways of demons.

He was a great talker and good at languages. He mastered Latin pretty well and could pray in Latin. Einhard said he understood Greek better than he spoke it, but this was in an age when any knowledge of Greek was becoming unusual in the west. Charlemagne was hungry for education in the liberal arts—the foundational subjects of grammar, logic (philosophical argument), and rhetoric—established long ago in the Roman educational system. He went to grammar classes with an old tutor, Peter the Deacon. He was naturally gifted at mathematics.

Famous scholar Alcuin (c. 735/40–804) entered this picture in the 780s, when he met Charlemagne on a journey back from Rome. The ruler invited Alcuin to join his court. He was not the first intellectual Charlemagne had recruited, but he was the first to stay.

Alcuin may not have intended to stay either, but his first period as a courtier seems to have lasted for three years or more. The court was in perpetual traveling motion, so he had the chance to meet other European intellectuals. In the 790s when the court settled permanently in the new palace Charlemagne built at Aachen, Alcuin remained for a year or two. At this time he may have had important influence on the intellectual culture of the court. Charlemagne certainly seems to have found him helpful with astronomical calculations.

Charlemagne was sufficiently anxious to foster education that he required cathedrals to run schools for their canons (clergy belonging to the cathedral). He was alive to the danger of allowing his empire to fill with uneducated clergy, and he needed literate civil servants. But in reality many notable achievements came after his time. (See “For the love of learning,” pp. 24–29).

Charlemagne was a regular churchgoer, always at matins, evensong, and the Eucharist if he could manage it in the midst of his travels and battles. He was vigilant in insisting that worship be conducted properly, and he overhauled the order of service personally. That should have raised eyebrows. It was becoming important, in a Europe busy reorganizing itself, to be clear where the boundary lay between secular and spiritual authority.

Pope Leo III (reigned 795–816) certainly needed Charlemagne’s support. His election had been rushed amid factional infighting. The announcement of Leo’s election was sent to Charlemagne with a request for his help against the Lombards. Charlemagne wrote back setting out the balance of power: it was his job to defend the papacy, and the pope’s job to pray for the empire and the success of its armies. But the new pope was soon attacked by his rivals and thrown from his horse during a procession.

Helping out the pope

Leo fled to Paderborn (in modern Germany) to seek Charlemagne’s protection. Charlemagne tried to resolve the dispute. In the end he went to Rome himself and spent the winter of 800–801 there restoring order. Charlemagne had for some time been emperor in all except name, and now at the hands of the grateful pope, on Christmas Day 800 in the Basilica of St. Peter, he was made Holy Roman Emperor—a title that had lain vacant for over 300 years. The Christian Roman Empire founded in this way lasted until the sixteenth century.

Charlemagne was not a theologian but a man of affairs. As a Christian he saw it as his business to defend, protect, and enrich the church where he could and encourage those he conquered to be baptized as Christians too. He respected Rome’s power, though he visited Rome himself only four times in a reign of nearly half a century. He took special care for the Basilica of St. Peter. Using plunder from his warfare, he provided gold, silver, and precious stones for its enrichment, and he was eager all his life to see Rome returned to its former glory and the primacy he believed it should have.

The question of Roman primacy at this date was different from the way it later presented itself. In Charlemagne’s time the question was which of five ancient patriarchates should be chief, and in what way? The Greek part of the old Roman Empire had four: Alexandria, Antioch, Constantinople, and Jerusalem, while the west had Rome. Rome could claim preeminence because it was the See of the Apostle Peter, but the Greek patriarchs preferred to see this as a mere primacy of honor, not as giving the bishop of Rome authority over the Christian Church everywhere.

Charlemagne has become such an iconic figure in the history of early medieval Europe that it is easy to forget the difficulties he faced. We remember him today, from his fur-lined coat to his elephant to that Christmas morning when he received the imperial crown, because he created a new Europe, and yet one in which the marks of classical civilization remained. CH

By G. R. Evans

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #108 in 2014]

G. R. Evans was formerly professor of medieval theology and intellectual history at the University of Cambridge. She has published widely on medieval history and theology.Next articles

Charlemagne vs. the Saxons

Were the Saxon wars really driven by the desire to convert these pagans?

G. R. EvansHow the Irish saved (Carolingian) civilization

Irish scholars, bards, and scientists were recruited to serve in Charlemagne’s court

Garry J. CritesSacred kingship

The coronation of Charlemagne entwined state and church from his day to ours

Christopher FeeSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate