The storyteller

ONCE UPON A TIME . . . a long time ago—though not so long as you might suspect—there was a man who believed that stories must be told. For after all, he knew that was what had happened in the beginning: stories were told. Once upon a time . . . a long time ago, stories changed the world forever: in the beginning; in the days of Caesar Augustus; and ever since.

And so this man told stories too: some were of real events, some could have been, and others were pure fantasy. But all were shaped by an imagination that strove to make stories in imitation of the goodness and holiness of the Original Story Crafter.

A poor composition tactic, some would say. They would argue that goodness and holiness are boring elements in a tale and never as interesting as evil. Yet again and again, this man’s stories changed lives. They changed the lives of boys, girls, men, and women; the lives of anonymous readers and those well known: John Ruskin, Florence Nightingale, Oswald Chambers, Madeleine L’Engle, Hans Urs Von Balthasaar.

The storyteller wrote sermons, poetry, and essays too, and his disciples found them likewise full of treasures. But it was his stories that drew the most praise from his advocates. These stories—even the fairy tales—had truly changed their lives.

“My imagination was baptized”

The Princess and the Goblin, proclaimed journalist and philosopher G. K. Chesterton, “made a difference to my whole existence. . . . Of all the stories I have read, including even all the novels of the same novelist, it remains the most real, the most realistic, in the exact sense of the phrase the most like life.”

And Phantastes, about a scholar lost in fairyland, asserted critic and apologist C. S. Lewis, was a “voice which called to me . . . I knew that I had crossed a great frontier . . . my imagination was, in a certain sense, baptized.” When asked near the end of his life and career (in 1962) to list books that had most shaped his “vocational attitude” and “philosophy of life,” Lewis placed the works of Virgil, Boethius, George Herbert, and even Chesterton subservient to that tale about the fairyland wanderer.

Lewis explained that what he had found there went beyond the expression of things already felt. It arouses in us sensations we have never had before, never anticipated having, as though we had broken out of our normal mode of consciousness and “possessed joys not promised to our birth.” It gets under our skin, he said; it hits us at a level deeper than our thoughts or passions, troubles oldest certainties till all questions are reopened, and shocks us fully awake.

Some story. And the storyteller? George MacDonald.

One of the most striking facts about the eminent status granted MacDonald by Chesterton and Lewis is just how many other stories they had read. These men were obsessive bibliophiles, reading more than most of us ever could or would. Their brains were legendary; their standards exacting. While they did not claim MacDonald to be the best writer they had encountered, they did declare that his books revolutionized their lives as no other books had.

In him they found a scholar who explained that the divine gift of imagination is not merely the partner to reason, but its flip side; imagination and reason are mutually dependent. But it must be exercised and practiced. Lewis noted in his well-marked copy of MacDonald’s Dish of Orts: “Repression of Imagination leads not to its disappearance but to its corruption.”

MacDonald reminded readers that imagination forms a powerful component of human identity. How and where and why we exercise it shapes our present, future, past—and affects every relationship, with all God’s creation, human or otherwise. He sought to exercise that imagination in a manner pleasing to God and in a way that would invite, even compel others to do the same. Chesterton and Lewis were compelled.

“A wise Imagination,” wrote MacDonald, “is the presence of the spirit of God.” But his essay “The Imagination: Its Functions and Its Culture” convinced Lewis the imagination requires cultivation in the presence of goodness and holiness.

To truly understand how this is so, we must experience it. Lewis wrote that the best way to grasp how MacDonald’s presentation of goodness and holiness can have such dramatic impact is to read and experience for oneself stories such as Sir Gibbie, The Wise Woman, or Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood. Mere explanation will not suffice.

That MacDonald could craft such stories was not simple talent. He diligently studied other presentations of goodness and holiness: he examined, explored, compared them. He considered their representation within Scripture as well as works by Dante, Chaucer, Sidney, Shakespeare, Herbert, and Tolstoy.

Careful critic and scholar

And he endeavored to practice what he found, convinced that “nobility of thought” would corrupt without “nobility of deed.” What Lewis learned over years of reading MacDonald, what changed his life and helped prepare him to receive the Gospel, came from MacDonald’s care-filled labor. MacDonald’s vocation, his prime profession for decades, was as a literary scholar. And his critical methods, particularly his determination to draw his readers into conversation with literary greats from Plato and Paul to Bunyan and Coleridge, left their mark.

While each of our seven sages engaged with MacDonald in one fashion or another, Lewis claimed the greatest debt. In his Anthology of MacDonald, Lewis sounded a bit exasperated that his readers had not taken him at his word:

In making this collection I was discharging a debt of justice. I have never concealed the fact that I regarded [MacDonald] as my master; indeed I fancy I have never written a book in which I did not quote from him. But it has not seemed to me that those who have received my books kindly take even now sufficient notice of the affiliation. Honesty drives me to emphasize it.

Yet Lewis’s attempt to direct his readers to one of his primary influences continues to be largely ignored. That an author of fairy tales and fantasies could have such profound impact on the famed Oxbridge apologist often evokes a slightly patronizing response: isn’t Lewis exaggerating a tad? But a close reader of both authors cannot deny the truth of the admission.

Lewis had imbibed MacDonald’s fairy tales since childhood, a shared love that was one of the first things drawing him to become friends with Tolkien. Upon adult reflection Lewis realized that “the quality which had enchanted me in [MacDonald’s] imaginative works turned out to be the quality of the real universe, the divine, magical, terrifying, and ecstatic reality in which we all live.”

Love of goodness

Returning to Lewis’s remark that MacDonald’s Phantastes “baptized” his imagination in 1915 at the age of 17, it is helpful to remember that he spoke as an Anglican for whom baptism was not a premeditated, full-immersion, public declaration. Instead the image is of an infant brought to the font on another’s initiative; the holy commencement of something unexpected, yet full of promise. “Nothing was at that time further from my thoughts than Christianity.” In reading Phantastes Lewis “learned to love” goodness and discovered “a new quality”: holiness. It was, he later reflected, a beginning.

Having rediscovered MacDonald as a teenager, Lewis became a passionate fan. Letters to his friend Arthur Greeves teem with enthusiastic discussions of realistic novels as well as of fantasies. Lewis’s transition from student to professor did little to abate this fervor, not least because he kept finding fellow MacDonald admirers.

When Owen Barfield gave Lewis a copy of MacDonald’s book-length prayer-poem Diary of an Old Soul in 1929, Lewis confessed this was the first he had read the work properly: “[It] is magnificent. You placed the moment of giving it to me admirably, I remember with horror the absurdity of my last criticism on it, with shame the vulgarity of the form in which I excused it.” Lewis read each stanza, allocated for each day of the year, faithfully—like a devotional.

At the end of 1930 and still preconversion, Lewis bought what would become his favorite MacDonald novel: What’s Mine’s Mine. Within the text, two brothers struggle with concepts of faith, commitment, obedience, and love. They fight against community destruction and environmental degradation. They discuss Isaiah, Euclid, and Virgil. All these themes reiterated what Lewis had read elsewhere in MacDonald as a child and young adult.

By the time Lewis became a Christian, he had been repeatedly exposed to these emphases in MacDonald. He wrote: “When the process was complete—by which, of course, I mean ‘when it had really begun’—I found out that I was still with MacDonald and that he had accompanied me all the way and that I was now at last ready to hear from him much that he could not have told me at that first meeting. But in a sense, what he was now telling me was the very same that he had told me from the beginning.”

Those willing to meet MacDonald themselves in the originals should remember he was a Victorian author, using nineteenth-century language and metaphors. Thus his readership dwindled in the twentieth century. But it is rising significantly in the twenty-first. Chesterton predicted that the time for readers to truly understand MacDonald had yet to come: the recent surge suggests he was correct.

Perhaps MacDonald meets a need recently identified by author Toni Morrison. She cautioned of “the death of goodness in literature” and described a cultural obsession with evil. Denying that goodness is monotonous, she pledged to write novels in which goodness has “life-changing properties,” “never trivial . . . never incidental.” She acknowledged it won’t be easy; evil is easy.

In the beginning was the story

But what she sought was exactly what Chesterton and Lewis found in MacDonald. Both knew too well the attraction and compulsion of literature that gives evil an intellectual platform. Yet MacDonald convinced them what Morrison urged her Harvard audience to believe: that goodness is never trivial, but life-changing—as it was in the beginning; in the days of Caesar Augustus; and is now and ever shall be.

MacDonald gave considered attention throughout his works to the relationship between imagination and science. But he was clear that in the beginning there was a Story in which we were called to participate. Even in his novels he reminded the reader that once upon a time the Original Story Crafter invited us to imagine with him; and that in the days of Rome, Christ reminded us to see how others imaged and re-imaged truths.

MacDonald also drew our attention to other storytellers who used their imaginations to communicate Gospel truths to their particular cultures and eras. He was convinced that those who are attentive to such conversations throughout the ages will be better able to communicate to their own eras. Chesterton and Lewis stand as witnesses.

As MacDonald the storyteller (and essayist, sermon writer, poet, professor, hymnist, anthologist, and literary critic) continues to receive renewed attention, perhaps the recommendations of Lewis and Chesterton will become a mere footnote, and readers will independently discover the transformative power of his work. Even for Lewis endorsement was only a start. He wrote of MacDonald, “I dare not say he is never in error; but to speak plainly I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself.”

And then he told some stories to explain: not so very long ago. CH

By Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson is the author of Storykeeper: The Mythopoeic Making of George MacDonald (2015); lectures internationally on MacDonald, Tolkien, and Lewis; and is on the board of SEVEN: An Anglo-American Literary Review. For more, see kirstinjeffreyjohnson.com.Next articles

What C. S. Lewis learned from his “master”

Lewis’s recommendation to seekers: read George MacDonald

Kirstin Jeffrey JohnsonLearning what no one meant to teach

The educational experiences of C. S. Lewis (1898-1963)

Michael WardDid you know?

MacDonald’s players, Tolkien’s grave, Chesterton’s pajamas, and Lewis’s hat

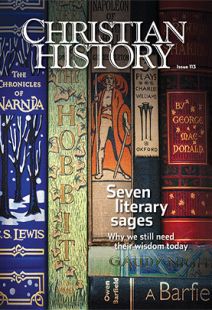

the editorsEditor's note: Seven literary sages

How much did C.S. Lewis and his friends and mentors change the society around them?

Jennifer Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate