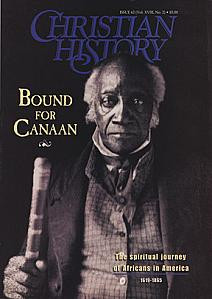

ONCE A SLAVE, AMANDA SMITH'S FAITH BROUGHT HER WORLDWIDE FAME

[Above: Amanda Smith, adapted from the frontpiece of An Autobiograph The Story of the Lord's Dealings with Mrs. Amanda Smith the Colored Evangelist. Chicago: Meyer & Brother, Publisher, 1893. public domain]

“I WILL PRAY once more,” said Amanda to herself, “and if there is any such thing as salvation, I am determined to have it this afternoon or die.” It was 1856. She set the dinner table and went to the cellar to pray, half expecting that her family would find her dead, because she had prayed before without receiving assurance of acceptance with God. She had even overcome deep reluctance and gone to the altar at her church, but came away as miserable as when she went.

In the cellar, her prayers once again seemed futile. Finally, in desperation and believing that God would strike her dead because she had promised to get saved or die, she looked up and said, “O, Lord, if Thou wilt help me I will believe Thee.” In the act of telling God that she would, she came to belief. “O, the peace and joy that flooded my soul!” she said. From that day forward, Amanda had two ambitions in life: to know God better and to tell others about him.

Born a slave in Maryland in 1837, Amanda was freed when she was three. Her family moved to Pennsylvania and their home became a station on the Underground Railroad. Amanda witnessed terrifying incidents when slave trackers demanded fugitives—or caught them. One of Amanda’s free-born sisters was sold into slavery while visiting an aunt in Maryland. Amanda had to borrow $50 to buy her back. Given these experiences, she knew slavery, and when she experienced salvation in Christ, she praised God that she had been freed twice.

However, she was unwise and even disobedient. “O, I would God I had always obeyed Him, then would my peace have flowed as the river, but many times I failed.”

Before her conversion, she had married a man who was kind to her—when he was sober. He went to war and never returned. Because Amanda wanted to share the gospel, she next married a deacon who promised to become an evangelist. He was lying and he eventually abandoned her. She realized that she had not cleared the marriage with the Lord. As a consequence, she experienced poverty and had to work long hours, starving herself so her children might eat. This taught her to bring every detail of her day to the Lord in prayer. All but one of her children died in infancy, the result of lying in damp rooms while Amanda sweated over laundry. The one daughter who reached adulthood died in her early twenties.

One Sunday in 1868, Amanda felt impelled to go hear John Inskip preach. She believed Inskip’s claim that God could bring every thought and action into subjection to Him, and asked God for this. Waves of joy flooded her soul. Although she was the only black person in the church and afraid of white people, she shouted aloud. On the way home she also found courage to tell some haughty black women what the Spirit had done for her: “And they were speechless.”

Amanda believed that she was led by the Holy Spirit. Around 1869, the Lord instructed her to go to a fair. She questioned this impulse as she was not a fair-goer, but she went, praying for direction. “I got up and went and stood at the top of the stairs where the people were coming up . . . then came two young men full of glee. The Spirit seemed to pick out one especially, and said, ‘Speak to that young man.’” She did, but he respectfully brushed her aside. All night she felt that she must pray for him. The next morning she learned he had died.

The year following her sanctification, Amanda received a command from the Lord to preach. Women preachers were not yet widely accepted—much less black women. Yet, dressed plainly in Quaker-like garb, she began speaking in African Methodist Episcopal (AME) churches. Her stirring songs, her vivid testimonies and her obvious faith spurred many others to seek salvation and sanctification. White people invited her as a speaker to their camp meetings. Soon she had invitations from around the world. This self-educated ex-slave went on to win souls on five continents and to challenge Christians to live lives consistent with their beliefs.

Bishop James M. Thoburn of Bombay asserted that he learned more from Amanda that was of actual value to him as a preacher than from any other person he ever met. After her foreign travels she worked for eight years as a missionary in Liberia and West Africa, where revival broke out. “The people came from all directions. We went on for two weeks without a break. We had several all-night meetings. . . . Some old men were converted that were never known to pray or be serious before.” Amanda did not return to the States until 1890, when malaria, rheumatism, and arthritis made it impractical for her to labor in Africa. She was fifty-three years old.

Old age and ill health did not shelve Amanda. After writing her autobiography, which was published in 1893, she opened a home in Chicago for black orphans. To raise support for it, she returned to preaching and singing in churches. She died in on this day, 24 February 1915, of a paralytic stroke at the age of seventy-eight. Her autobiography, with its homey details of her struggle for survival and hunger for holiness, became a classic in women’s studies and is an inspiring glimpse into the mind of a soul that sought God.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For more about the African experience in America, take a look at Christian History #62, Bound for Canaan