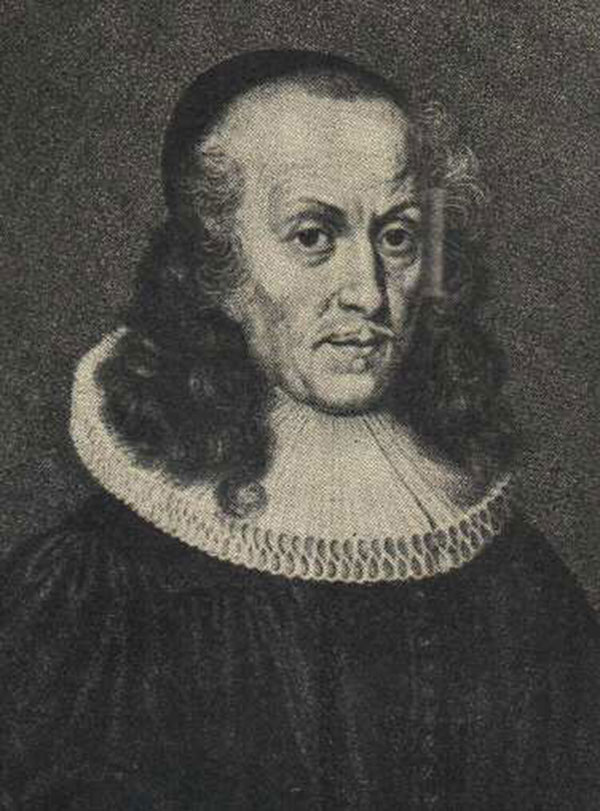

PHILIPP SPENER WANTED CHRISTIANS TO PRACTICE HEART-FELT FAITH

[ABOVE—Philipp Spener—Magnus Manske / public domain Wikimedia File:Philipp Jakob Spener.jpg]

In 1666, the council of Frankfort-on-the-Main invited Philipp Spener to become their city’s head pastor. In this position he would supervise eleven other Lutheran ministers, some considerably older than his thirty-one years. The city had decided that its church ministries should be overseen by a doctor of theology.

Spener faced a tough decision. Scholarly, reserved, and pious, he had previously reneged on a promise to head a church because he shied from dealing with troubled souls. Subsequently, he had been content to act as an assistant pastor with few counseling responsibilities. Moreover, he was reluctant to leave Strasbourg where he had a network of friends and family and where he hoped to teach at the university. Consequently, Spener advised Strasbourg of Frankfort’s offer, hinting that his alma mater should offer him a job. When it did not, he accepted the Frankfort call.

Taking a low-key approach to overseeing the other pastors, Spener set out to inspire and transform lives through sound teaching and preaching. His first sermon took as its text “I am not ashamed of the Gospel of Christ.” Unhappy that the Lutheran lectionary neglected many Scripture passages, he prefixed its assigned lessons with an “Exordium” in which he taught through Paul’s Epistles. He catechized children. Soon adults were joining the classes, saying they learned more in them than from a dozen sermons such as were preached in most pulpits. Spener wrote a popular children’s book on Luther’s catechism. He revived confirmation as a means of encouraging youth to understand and commit themselves to the gospel.

Three years after coming to Frankfort, he preached on the text, “Except your righteousness exceed the righteousness of the Scribes and Pharisees, ye shall in no case enter into the Kingdom of Heaven.” Soon groups formed, seeking deeper life. Fearing factions and doctrinal wrangles, Spener led the meetings himself. Later he formed accountability groups whose members confessed to each other. Other pastors throughout Germany began to imitate Spener’s practices, implementing the Pietist movement.

In 1675 Spener published Pia Desideria, or Pious Desires. The book was aimed at reducing party spirit, the worldliness of princes, and the spiritual ignorance of the common folk. Its principal remedy for these ills was making church people more aware of the entire Bible. He urged lay Christians to recognize their spiritual priesthood. He wanted all Christians to realize that faith is a matter of the heart, not merely ritual and head knowledge. He advocated widespread prayer. Theological students, he said, should be better trained for the practical difficulties they would encounter. And sermons should edify hearers, not merely argue doctrine or flaunt learning.

His book was eagerly received, but, as his biographer Francis Frederick Walrond would write, “many of those who applauded Spener at the beginning of his work turned fiercely against him when they found how much that work implied. Men may feel the grasp of God upon their hearts, and presently become all the more hardened to resist it.” Consequently, Spener suffered opposition and slander. One of his books was censored. Despite his warnings one of his small groups broke away from the Lutheran Church, saying they could not worship with sinful, unconverted hypocrites. Spener was accused of promoting schism.

He was also vilified because he accepted Calvinists as fellow Christians. Given Luther’s well-known inflexibility toward the Swiss reformers, Spener was regarded as virtually a heretic. He did not ease his situation by advocating the reduction of prejudices and discrimination against another unpopular group—Frankfort’s Jews.

Invited to become court preacher for the Elector of Saxony at Dresden, he accepted, but there he found himself battered by godless theologians. Against their powerful opposition, he could only preach the truth, declaring he had “nothing but the power of God” to sustain himself. Courtiers poisoned the elector against Spener and the elector tried to make him resign. Eventually Spener accepted a post in Berlin, whose Calvinist ruler treated Lutherans fairly.

Spener spent the last fourteen years of his life in Berlin, faithfully catechizing, overseeing churches, and training a new generation of pastors. He helped bring into existence the evangelical University of Halle. Because the university promoted faith over formalism and did not dwell on Lutheran doctrinal disputes with Calvinists, the Theological Faculty of Wittenberg found Spener guilty of two hundred and eighty-three errors. Rigid Lutherans claimed that “under a pretense of devotion and holiness of life” Spener and Halle were destroying the church. They pointed to fanatics and visionaries who emerged across Germany claiming revelations. Spener was not responsible for them, but was blamed anyhow. Although Spener himself was not legalistic, other Pietists could be, and he was blamed for their rigidity. Under all such attacks he was gentle.

To the end of his life, he spent hours a day in intercessory prayer. He was able to do this and accomplish his other duties because he did not waste a moment. Ironically, he also became Germany’s leading counselor of souls, consulted in person and by mail. He penned so many letters of spiritual advice that he had to request a governmental exemption from postage.

In 1704 Spener experienced faintness. He would live only a few more months. The evening before his death he had Christ’s high-priestly prayer (John 17) read to him three times. He died on this day, 5 February 1705. His theological enemies claimed Spener had not entered the rest of the Lord. Later generations have judged him more generously. He is often called the “Father of Pietism.”

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

God's Glory, Neighbor's Good: The Story of Pietism can be streamed at RedeemTV. Also available at Vision Video.

Learn more about Pietism in Christian History #10, Pietism: A Much-Maligned Movement Re-Examined