READING BETWEEN THE LINES OF NOBLE CLOTILDE’S CHARTER

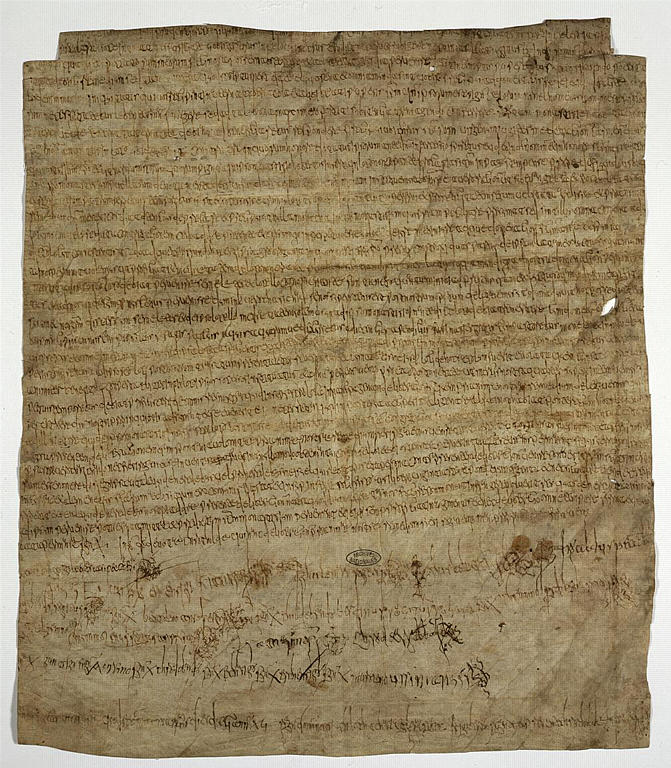

[Above: The charter of Clotilde founding the abbey of Bruyères-le-Châtel dated 10 March 673—Archives nationales / public domain, Wikimedia File:Charter of Clotilde.jpg]

ON THIS DAY, 10 March 673, a French noblewoman gifted land to found a nunnery at Bruyères-le-Châtel. The charter was witnessed by a notary, two high-ranking clergymen, and several secular signatories. In the charter, a certain Clotilde deeded the land and appointed her niece, Mummola, as the institution’s first abbess.

Clotilde’s charter presents us with a slice of seventh-century religious life. It also holds special interest because it is one of only a handful of verified French legal documents that have survived from that period. In fact, it is the oldest French parchment to survive from the seventh century. Official documents were usually recorded on papyrus.

The charter also poses mysteries. Who was Clotilde? Was she related to the Merovignian royal dynasty? Had she and her husband separated to devote themselves to religious works? Why was the Bruyères nunnery never again mentioned in history? How and why did its charter wind up at St. Denys, Paris? Scholars have only conjectures for each of these questions.

The charter suggests a tale of woe. It employs a Latin legal term (ex luctuoso) that refers to property that returns to a mother upon the death of a son. It also reveals concern that relatives might try to seize the property, for a strong curse is laid on anyone who attempts to do so.

But if anyone—I do not believe this will happen—if myself or any of my heirs and great-heirs or any other person to the contrary endeavors to go against this charter, may he incur the wrath of the Holy Trinity, that he stand, excommunicated, away from the thresholds of the churches, and that he also pays to the treasury, our associate, twenty pounds of gold, fifty of silver by weight, and that so he cannot claim what he claims….

We learn something of the state of seventh-century education: half of the witnesses could not write. Among those who could was Saint Agilbert, bishop of Paris, better known for his earlier years in England. Bede’s history tells of Agilbert’s stormy bishopric in the days of King Coenwalh of Wessex.

Finally, the charter opens a window onto the spiritual outlook of the day. By its terms the nuns were to pray attentively for kings, for the church, and for Clotilde’s soul. Clotilde explicitly stated her belief (based on misunderstood Scriptures) that she could erase her sins by donations and purge her crimes by alms. And, showing the importance of tangible mementoes as props to medieval faith, the charter provided for the nunnery to house relics.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For true stories of more women who changed the world, read our book Great Women in Christian History

To find out what Christian practice looked like for Medieval women, see Christian History # 30 Women in the Medieval Church and for women later in the Middle Ages, see Christian History #127 Medieval Lay Mystics