A renewed and global faith

[Cano’s Entombment of Christ; Atheneum]

IMAGINE A CONFESSIONAL: the rows of little doors; the dark ornate wood; the screens that hide the confessor from the penitent. Whether you’ve knelt inside one on a Saturday afternoon or merely seen one as a tourist or in a movie, they represent the Catholic Church in the minds of many. And until the Council of Trent, they didn’t exist.

I do confess

Confessionals were created after Trent for women penitents, lest their confession of sexual sins be impeded by the awkwardness of speaking face to face with a man. (Later the confessional box came to be used by male penitents as well.) In fact much of what shaped Catholicism between the sixteenth century and the twentieth traces back to the bishops at Trent and their hopes of preventing a wide range of abuses among the clergy: ignorance, fornication, greedy careerism, and absenteeism.

Trent transformed and standardized the priesthood itself with the creation of seminaries to educate diocesan priests. Though men could still be ordained at a bishop’s discretion even if they had not attended seminary, the new mandate did, over time, help to create a better-educated priesthood.

Seminaries also enforced celibacy and helped to stamp out clerical misbehavior. A new ideal arose of the austere, sober, prayerful parish priest, who lived in a rectory, wore clerical garb, and devoted countless hours to pastoral work such as administering the sacraments.

As in Protestant territories, so too in Catholic ones—enforcement of doctrinal orthodoxy became in the sixteenth century a major concern of both church and state. In the late fifteenth century, the Spanish Inquisition had been founded by the Spanish monarchy as part of its efforts to create a united Spain, uniform in religion. This meant, in practice, persecution and expulsion of Jews and Muslims.

Pope Paul III founded the Roman Inquisition in 1542 and charged it with rooting out supposed heresies, Lutheran or otherwise. But because of the aggressive guarding of royal prerogatives in Catholic kingdoms such as France, Portugal, and Spain, the Roman Inquisition had little authority outside central Italy. Catholic kings wanted to persecute their own heretics.

Though at times savage in their methods, both Inquisitions largely avoided the prosecution and persecution of alleged witches—otherwise a rampant activity in northern Europe, both Catholic and Protestant.

Who’s in charge here?

Protestant reformers disagreed among themselves about many things, but they all agreed on rejecting the papacy, either because it taught doctrinal error, set an appalling example of moral decay, or imposed an oppressive Roman bureaucracy on Christendom—exacting taxes and fees from poor Christians for the benefit of a worldly, war-mongering pope and his curia (court).

Order Christian History #122: The Catholic Reformation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Yet the Council of Trent said little about the papacy. Bishops themselves disagreed about how papal authority related to the authority of heads of state and of national and local churches. The council did, in its closing session, ask for papal approval of its decrees, effectively placing implementation under papal control.

Popes often played a key role in fostering the development of new religious orders and reforming old ones. Paul III approved the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) in 1540 (see “Helping souls,” pp. 6–11). Unlike monks who belonged to a specific monastic community, Jesuits were to be tied to no particular place but rather available to be sent anywhere in the world where the needs were greatest. The pope, not the local bishop, was to do such sending.

Older religious orders also saw new reform movements emerge from within their ranks. The Capuchins, founded in 1528, aimed at making Franciscans more faithful sons of St. Francis of Assisi. Carmelite nuns, who had come into being in the fifteenth century, were reformed in the sixteenth by Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582) in Spain. In 1562 she founded a branch of the order devoted to silence, prayer, and poverty in a cloistered community.

Other women founded new communities that worked outside the boundaries of cloisters as teachers and nurses among the people, especially the poor. The Daughters of Charity, founded by Louise de Marillac and Vincent de Paul in 1633 in France, was an excellent example of this new model of female religious life.

Priests were also newly exhorted by the council to explain what the church taught about faith and morals; lay catechists were trained to do this as well. The Catholic catechesis focused intensely on the seven sacraments, especially the Eucharist and the sacrament of penance.

An emphasis on the Word and on preaching is often, and rightly, associated with the Protestant Reformation, but Catholic reformers also insisted on the centrality of the pulpit in explaining Scripture, teaching doctrine, and encouraging people to reform and correct their sinful, immoral lives.

The Council of Trent identified preaching as the principal duty of bishops, a major change for many sixteenth-century bishops—who had been accustomed to spending little time on pastoral duties while they lived in luxury, frequented prostitutes or mistresses, and perhaps did not even set foot in their dioceses.

Saints and angels

Protestant reformers had stressed Christ alone as mediator between God and humanity; Luther, Calvin, and others rejected a cult of the saints that emphasized praying to saints as intercessors and as miracle workers who could obtain cures and other favors from God. After Trent came a major renaissance of this Catholic devotion to saints as intercessors and exemplars of Christian life. Saints were understood by the devout to bridge the gap between heaven and earth, accessible and available in ways a more distant God might not be.

In the post-Trent era, bishops were supposed to root out any superstitions in devotion to saints, even as they promoted a renewed attention to this devotion. Angels were also imagined as filling the space between earth and heaven, descending from heaven as God’s messengers and ascending with humanity’s prayers to God. Children were taught that they each had a guardian angel looking after them and helping them to be good.

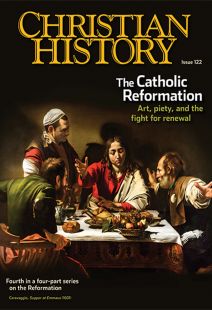

Concerned with idolatry, some Protestant reformers encouraged iconoclasm, the destroying of images of God, Christ, or the saints (see CH issue 118). But after Trent, Catholics ushered in a sustained renaissance of visual arts. Michelangelo (1475–1564), Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610), Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), and others created new representations of Christ, Mary, and the saints—including freshly canonized ones such as Ignatius and Teresa—in painting, sculpture, stained glass, and other media (see “Picturing saints,” pp. 16–18).

The invention of the printing press in the fifteenth century has often been cited as indispensable to the Protestant Reformation. Could Luther have accomplished much without it? One could ask the same question about Catholic reformers. Bishop Francis de Sales (1567–1622; see “Remaking the world,” pp. 40–43) first published the best seller Introduction to the Devout Life in 1609 in French. Translated in his own lifetime into other major European languages, it was aimed at laity seeking to live a holy life in the world: “It is an error, or rather a heresy, to wish to banish the devout life from the regiment of soldiers, the mechanic’s shop, the court of princes, or the home of married people.” Jean-Pierre Camus (1584–1652), a disciple of de Sales and also a bishop and popular preacher, published some 250 books in his lifetime, many going through multiple printings and translations.

To boldly go

Meanwhile, from the early 1500s, Catholic missionaries had been voyaging with Portuguese and Spanish explorers and colonizers to the Indian and Pacific Oceans and across the Atlantic. Soon European Catholic intellectuals were struggling with new questions not dealt with at Trent. Was enslavement of natives in the Americas morally acceptable? Were non-European races fully human? Could Mass be celebrated in Asian languages? Could Christianity be distinguished from European culture? For Catholics the challenges posed in northern Europe by the Protestant Reformation and addressed at Trent were eventually eclipsed by matters more global. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #122 The Catholic Reformation. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Thomas Worcester, S.J.

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #122 in 2017]

Thomas Worcester, S.J., is professor of history at the College of the Holy Cross, the author of Seventeenth-Century Cultural Discourse, and the editor of the Cambridge Companion to the Jesuits.Next articles

Christian History Timeline: The Catholic Reformation

The Christian History Timeline compiled from issues 5, 12, 34, 39, 48, 115, and 118, with additions by the editors

the editorsDefender of God’s justice

Arminius questioned some aspects of Reformed faith, but he never meant to launch a movement

William den BoerSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate