“We still make by the law in which we were made”

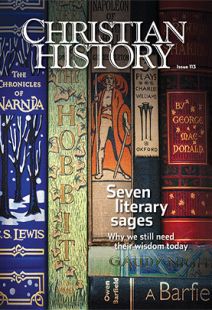

SAYERS was not the only one of the seven sages to turn her attention to the making of things. Tolkien famously invented the distinctive term “subcreation” for the making of a secondary, fictional world through active human imagination. Such secondary worlds are creatively taken from a primary reality made by God, whose image we bear, and are thoroughly consistent and plausible on their own inner terms.

Tolkien thought that subcreation is at the heart of what he defined as “fairy story,” and fairy story, he believed, represents the ultimate pattern of story-telling. For him the highest function of art is its creation of convincing secondary worlds. In such subcreation the human maker imagines God’s world after him, just as the early scientist Johannes Kepler believed he was thinking God’s thoughts after him. In one poem (addressed to C. S. Lewis while Lewis was on the road to conversion), Tolkien wrote of the human power to imagine both good and evil:

Though all the crannies of the world we filled with Elves and Goblins, though we dared to build Gods and their houses out of dark and light and sowed the seed of dragons, ‘twas our right (used or misused). The right has not decayed. We make still by the law in which we’re made.

Inspired by his friend’s invention of Middle-earth with its complex geography, history, and languages, eventually Lewis eagerly exercised his own “right to subcreate” the land of Narnia. Lewis, like Tolkien, became convinced that, through story, the real world becomes a more magical place, full of meaning. We see its real pattern and color in a fresh way—a renewed view of reality in all its dimensions. This applies to individual realities like hills, rivers, and stones, as well as to the cosmic—the depths of space and time itself. The successful creator of fairy story, Tolkien wrote, “makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is ‘true’: it accords with the laws of that world.”

In subcreating, the imagination employs both subconscious and conscious resources of the mind. Tolkien thought this especially true with regard to language, which seemed to him (as it did to Barfield) intimately connected to the whole person, not just to the mind. Subcreation allows powerful archetypes and universal themes to become part of artwork; something abstract in thought becomes particular and definite in the invented world. Universal truths, especially, take form as myths while retaining truths. Successful fairy story also offers consolation, leading to joy, as grace given from beyond the world is tasted. Tolkien characteristically wrote that “all tales may come true” because of the subcreative link between human and divine making.

Not only did Tolkien see the craft of the storyteller as a gift and a blessing, but also all skilled “making” when used for good, whether the skillful hands and eyes are those of humans, dwarves, or elves. Tolkien thus celebrated hobbit Sam Gamgee’s ability as a gardener and a forester as well as a storyteller.

As Frodo tells Sam in The Lord of the Rings’ concluding chapter: “Your hands and your wits will be needed everywhere. You will be the Mayor, of course, as long as you want to be, and the most famous gardener in history; and you will read things out of the Red Book, and keep alive the memory of the age that is gone, so that people will remember the Great Danger and so love their beloved land all the more. And that will keep you as busy and as happy as anyone can be, as long as your part of the Story goes on.”

By Colin Duriez

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

Colin Duriez is an author and poet living in the Lake District of England.Next articles

Friends, warriors, sages

How seven writers gave us stories that endure, imparting truths that never fade

the editors with Alister McGrath, Chrystal Downing, Colin DuriezThe storyteller

The stories of George MacDonald (1824-1905) showed goodness and holiness to Lewis and Chesterton—and show those same things to us

Kirstin Jeffrey JohnsonSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate