The Bible Riots

ON A SPRING NIGHT in 1844, the men and boys of St. Patrick’s parish in Philadelphia manned the roof of their church, rifles in hand, waiting for an anticipated attack that never came. St. Patrick’s was spared, but other churches were not: St. Michael’s at Second and Jefferson and St. Augustine’s on Fourth below Vine were engulfed in the flames of hatred during May and July of 1844.

This was not the first act of terror against American Catholics. In 1834 an angry Boston mob had burned down a convent because of Catholic protests against required readings from the Protestant KJV in public schools. And earlier in 1844, Roman Catholics in New York had also objected to the reading of the King James Bible in their schools. This helped to inflame the anti-immigrant “Know Nothing” party in a crusade against Irish Catholics in Philadelphia.

The “Know Nothing” term reflected the secret style of organization. If someone was asked about the party’s activities, he responded: “I know nothing.” The party insisted that all foreigners should be required to wait 21 years before being permitted to vote, that the Bible should be used in public schools to teach reading, that church and state should remain separate, and that only native-born Americans should be appointed to office.

The fears of the Know Nothings seemed validated when a rumor spread that the Catholics in Philadelphia wanted the King James Version of the Bible removed from the public schools. In denial of the charge, Francis Patrick Kenrick, Catholic bishop of Philadelphia, made a public statement on March 12, 1842: “Catholics have not asked that the Bible be excluded from public schools. They have merely desired for their children the liberty of using the Catholic version in case the reading of the Bible be prescribed by the controller or directors of the schools.”

The troubles began May 3, 1844, when the Know Nothings held a meeting in the predominately Irish Catholic district of Kensington in Philadelphia. Some residents attempted to attack the people on the platform. Three days later the group reassembled; a quarrel arose with onlookers and a pistol was fired. There was an answering shot from one of the windows of the hose-house of the Hibernia fire company, and before long there was a full-scale battle.

On May 6, more nativists arrived in the area and a fight broke out in the market, resulting in the death of two party members. As a result, a few Catholic homes and the School of the Sisters of Charity were attacked. The next day the nativists were back in full force, destroying the market, more homes and the Hibernia fire station. The mayor called the militia and things quieted down a bit. But the following day the convent and St. Augustine’s Church were burned: “Pew led the fire to pew, the galleries caught and at length the flames broke forth from the roof and the windows in front, and finally the steeple was on fire, and when the cross which crowned the height yielded to the flames and fell in, plaudits arose with savage exultation from many in the streets.” Firemen, under orders from the Know Nothings, let the buildings burn.

If anything good can be said to come from such brutality, at least the riots fed rising opposition to nativist groups such as the Know Nothings, resulting in a loss of popular support. The Know Nothings, despite having a strong coalition in place, were astounded when the Democratic party swept the election on October 9, 1854. The following year the Know Nothing Party renamed itself the American Party.

More trouble over Bible reading in schools

In a sense, the “Bible Wars” did not end after those violent days of 1844. In 1886, Catholic parents in Edgerton, Wisconsin, petitioned their local school board to stop daily readings from the KJV. The school board countered that “to read the Bible without comment was non-sectarian; to stop reading it because it offended Roman Catholics was sectarian.” After failing to convince the school board to end the practice, the parents took their case to court.

In November 1888 the circuit court decided that the readings were not sectarian because both the KJV and Catholic translations were of the same work. The parents took their case to the Wisconsin Supreme Court. In the famous action known as the Edgerton Bible Case, the judges overruled the circuit court’s decision, concluding that it illegally united the functions of church and state. In the end, the Wisconsin Supreme Court reversed a ruling in favor of the parents and forbade local boards to mandate readings from the KJV.

The Edgerton Bible case was not the only, or even the first, challenge to sectarian religious practices in public schools, but it was especially well researched and well argued by the parties involved. Seventy-five years later, when the U.S. Supreme Court banned prayer from the public schools in 1963, the Edgerton Bible case was one of the precedents that Justice William Brennan cited.

By Ann T. Snyder

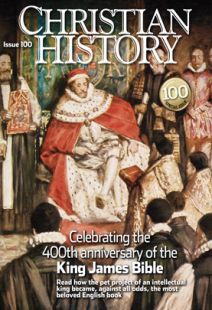

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #100 in 2011]

Next articles

King James Version: Recommended Resources

If this issue has piqued your interest in the KJV, here are some further windows into the history, language, and legacy of this translation

The EditorsEditor’s note: People of faith in America

American christianity is, at the very least, odd

Jennifer Woodruff TaitAmerican religion 2.0

What will survive? What will die? What will be transformed?

Chris Armstrong, R. Scott Appleby, Martin Marty, Molly WorthenSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate