Cosmic worship, sanctified matter, transfigured vision

“GRACE IS EVERYWHERE.” So testified the dying priest in Georges Bernanos’s The Diary of a Country Priest (1936), a gritty, tragic tale of an ordinary man’s journey to God. Though deprived of the church’s final sacrament, the priest had no concerns, for he found it all around him in the “light and dazzling beauty” of common roads and kicked-up dust.

Freed slave Sojourner Truth (c. 1797–1883) also saw something extraordinary in the ordinary, writing, “’Twas God all around me. … An’ then the whole world grew bright, an’ the trees they waved an’ waved in glory, an’ every little bit o’ stone on the ground shone like glass; an’ I shouted an’ said, ‘Praise, praise, praise to the Lord!’ An’ I begun to feel such a love in my soul as I never felt before—love to all creatures.” Trees and pebbles as vehicles of grace—a possibility Jesus foresaw when he exclaimed “the stones will cry out” (Luke 19:40).

Many Christians remember a moment when a breathtaking sunset or a brilliant morning landscape struck them to the heart. The praise of God has at all times included an appreciation for creation’s beauties and blessings: the Westminster Confession (1646) calls nature a “manifestation of the glory of God’s eternal power, wisdom, and goodness.” We praise God, Christians of the past tell us, for the goodness of this world within which we live and by which God cares for us; a grand and glorious canvas on which the glories of God are displayed.

For some, while nature is charming, inspirational, and spiritually beneficial, it is ultimately utilitarian. Early church father Origen (c. 184–254) spoke of nature only as the context within which human spiritual development transpires; Augustine (354–430) also marginalized its intrinsic value in favor of a superior spiritual reality.

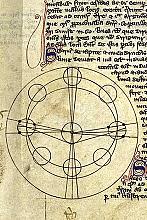

Other Christian thinkers approached nature as a book of general revelation, a manifesto of God’s power and character accompanying the book of Scripture. Hugh of St. Victor (1096–1141) wrote: “This whole visible world is a book written by the finger of God.” This concept became particularly relevant in late medieval natural philosophies, eventually leading to the birth of the scientific revolution (see “Reading the ‘book of nature,’” pp. 25–29).

Order Christian History #119: The Wonder of Creation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Against these more instrumental views, a silver thread of nature mysticism weaves throughout Christian history in three ways. Some mystics saw nature as a cosmic participant in the worship of God. Others described how the Incarnation makes the whole world full of God’s presence. Yet others talked about an internal transfiguration of the senses empowering them to see, taste, and hear nature in ways unknown to them before and thus to draw closer to God. All these mystics experienced nature not simply as a source of knowledge or power, or even witness or inspiration; but as a vehicle for the presence of God, a sacrament, an agent of spiritual reality. “Grace is everywhere.”

Nature worships

Beauty can move us to worship, but some Christians find nature’s beauty itself part of the worship: all creation joins together to sing God’s praises. In contrast to beliefs that the creation is ultimately doomed to destruction once its work is done, mystics argued that nature itself prays and has an eternal destiny. “Every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth and in the sea, and all that is in them” (Rev. 5:13)—emus and earthworms and giant squids and the local alley cat—has a part in the cosmic liturgy. So Gregory of Nazianzus (329–390) wrote in Dogmatic Poems:

The universal longing, the groaning of creation

tends toward thee.

Everything that exists prays to thee

And to thee every creation that can read

thy universe

Sends up a hymn of silence…

Thou art the purpose of every creature.

John Calvin (1509–1564) called creation the “theater of God’s glory” and agreed that it is not merely the environment within which humans can physically flourish or spiritually develop; it has a calling of its own:

For the little birds that sing, sing of God; the beasts clamor for him; the elements dread him, the mountains echo him, the fountains and flowing waters cast their glances at him, and the grass and flowers laugh before him.

As Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889; see p. 33) wrote, we are fellow worshipers, alongside the “kingfisher catching fire,” the exquisite “beauty of the bluebell,” and “the world-mothering air.”

Other Christians argued that we serve as priests to nature, mediating creation’s praise, giving voice to barking, mewing, bellowing, chirping, and even silent creatures. Leontes of Cyprus (eighth century) wrote:

Through heaven and earth and the sea,

Through wood and stone,

Through all creation visible and invisible,

I offer veneration to the Creator and Master.

For the creation does not venerate the maker

directly and by itself

But it is through me that the heavens declare the

glory of God.

Through me the moon worships God.

Through me the stars glorify Him.

Through me the waters, the showers of rain, and

the dews of all creation

Venerate God and give Him glory.

Anglican priest and poet George Herbert (1593–1633; see p. 21) also celebrated this cooperative adoration:

Beasts fain would sing; birds ditty to their notes;

Trees would be tuning on their native lute

To thy renown: but all their hands and throats

Are brought to Man, while they are lame and mute.

Man is the world’s high Priest: he doth present

The sacrifice for all.

Nature Is divinized

Many Christian nature mystics have found something even greater than fellow worshipers when they look at nature. For these the Incarnation, the coming of God made flesh, has raised nature to a new importance. These writers argued that all matter can bear the divine. Bread and wine, as wonderful and life-giving as they have always been, have the potential to be more than bread and wine; and so can every particle of matter.

Defenders of icons in the eighth and ninth centuries most famously gave us the theological justification for this concept. But some Byzantine Christians challenged the use of icons in worship, accusing those who used them of idolatry and violating the commandment against making images.

John of Damascus (c. 675–749) saw those who opposed images as rejecting the full implications of the Incarnation. He argued that Christians are not Manichaeans (adherents of the Persian religion that once attracted Augustine, who disparaged the material while pursuing the spiritual). On the contrary, John thought. In Emmanuel, “God with us,” God has “deified” all matter—the full cosmos.

For John and many others, the Incarnation was a sign of the universe becoming full of the presence of God: all the bits and pieces of this tangible world, sanctified by the God-Man, can now become conduits of divine grace. Wherever we look, we may see the substance of God’s actions—in wood, in paint, in robe, in cup—nature infused with “grace everywhere,” as John wrote:

I do not venerate matter, I venerate the fashioner of matter, who became matter for my sake and accepted to dwell in matter and through matter worked my salvation, and I will not cease from reverencing matter, through which my salvation was worked.

Some were quick to think this was a pantheism that worshiped nature, but John just as quickly said he was no pagan: “Just as iron plunged in fire does not become fire by nature, but by union and burning and participation, so what is deified does not become God by nature, but by participation.” Nothing is worthy of reverence in its own right, but everything can be a vessel of holy presence.

Our vision of nature is transfigured

Finally, many Christian nature mystics speak of a sanctified vision that alone can perceive the divine at work in creation. Nature is being transfigured, but so is our own ability to see it. Byzantine thinker Gregory Palamas (1296–1357) said that the miracle of the Transfiguration is the eyes of the disciples becoming opened to see. Normal vision became grace-filled vision:

Do you not understand that the men who are united to God… do not see as we do? Miraculously, they see with a sense that exceeds the senses, and with a mind that exceeds mind, for the power of the spirit penetrates their human faculties, and allows them to see things which are beyond us.

Palamas spoke of spiritual senses beyond the five physical senses and an “inner eye” that enables us to see the ineffable. Eastern Orthodox call this process of gaining vision “deification.” Through Christ salvation becomes a journey into the heart of God, enabling us to “see” God at work in and through creation and to participate in the divine nature (2 Peter 1:4). A story was told of Russian monk Seraphim of Sarov (1754–1833):

Father Seraphim … said: “My son, we are both at this moment in the Spirit of God. Why don’t you look at me?” “I cannot look, Father,” I replied, “because your eyes are flashing like lightning… .” “Don’t be afraid,” he said. “At this very moment you yourself have become as bright as I am … [and] are now in the fullness of the Spirit of God; otherwise you would not be able to see me as you do.”

Seraphim of Sarov had an unlikely predecessor in American theologian Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758). Though we rarely think of him as a mystic, Edwards spoke of a “spiritual perception” and “sanctified taste” that enable the true believer to see and discern the hand of God. He reveled in the newly awakened senses of the converted; they see things “with a cast of divine glory and sweetness upon them.”

These and many more—theologians and poets and priests, slaves and activists and soldiers—described the new creation that Paul spoke of as a cosmos redeemed and liberated to reflect the glory of God in unimaginable ways and to bring “grace everywhere.” Worshiping God through his creation, paying honor to the Incarnation, undergoing transformation; they ultimately had eyes to see it, ears to hear it, tongues to taste it. May we all. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #119 The Wonder of Creation. Read it in context here!

By Kathleen A. Mulhern

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #119 in 2016]

Kathleen A. Mulhern is executive editor at Patheos.com. She teaches in the areas of church history and spiritual formation at Denver Seminary.Next articles

The heavens declare the glory of God

Monks and nuns left us a legacy of spirituality honoring God’s creation

Glenn E. MyersAll life has its roots in me

Hildegard personifies the fire of God’s Spirit in this excerpt from her Book of Divine Works

Hildegard of BingenCreation Care, Did you know?

Christians have praised the display of God’s presence in the natural world since the beginning of the church

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate