From John Wesley to Ben-Hur

FOR YEARS IN ENGLAND, John Wesley sent out his preachers with a dual commission: as preachers, true, but also as booksellers, bringing an informed piety to their hearers. When Methodism crossed the pond, this impulse crossed with it. The average itinerant circuit rider brought sermons, news, and the sacraments to his preaching outposts. But he also carried a precious form of education and entertainment: books.

When he opened the first office of the Methodist Book Concern in 1789, Thomas Coke reflected: “The people will thereby be amply supplied with Books of pure divinity for their reading, which is of the next importance to preaching.” The Book Concern was the first American publishing house to systematically print and distribute evangelical books, from Bibles and hymnals to medical advice, across the nation—at a time when secular publishing remained in its infancy. And carrying books around in your saddlebag was not optional. The General Conference required all ministers to act as agents for all official Methodist publications.

A zeal for publishing books

But the endeavor might not have gotten off the ground without the tireless efforts of Nathan Bangs (1778–1862). Few individuals did more for Methodist publishing than Bangs. Born in Stratford, Connecticut, of old Puritan stock, Bangs joined the Methodists in 1800 and soon enlisted as an itinerant preacher and missionary to frontier areas (in those days southern Ontario and Upstate New York!), undaunted even by the outbreak of the War of 1812. He reflected, “I feel more strongly attached to this work than ever. . . . O my Soul enter into a fresh engagement to be more than ever engaged in doing the Master’s work.”

Bangs maintained this zeal throughout his long and productive life: writing 14 books, preaching, organizing camp meetings, founding the Methodist Missionary Society, and serving as president of Wesleyan University. When he first arrived at the Book Concern in 1820 to take charge, he found the 30-year-old institution deeply in debt and with only a few poorly selling books.

Bangs entered into the crisis with typical zeal and focus, providing the Book Concern with its own printing press, a bindery, and an office. In the 1820s and 1830s, he founded and edited Methodism’s major periodicals: the Methodist Magazine and Quarterly Review and the Christian Advocate. He also told Methodists their own story in his four-volume History of the Methodist Episcopal Church (1839–1842). They ate it up. By 1829 the Christian Advocate claimed 20,000 subscribers, the second highest number then recorded by any periodical in the world. No secular paper could boast a circulation higher than 4,500.

By 1860 the Methodist Book Concern published eight regional papers as well as German and Swedish editions, a quarterly intellectual review, a literary magazine, a missionary paper, a women’s magazine, and four Sunday school papers. The total weekly circulation of all official Methodist papers ranked with the nation’s most successful periodicals. The Methodist Western Christian Advocate, published from 1834 to 1939 in Cincinnati, outstripped every other paper in the region.

From revivals to curtains

All of the Book Concern’s periodicals shared a common agenda: “the spread of what we believe to be the genuine doctrines of the gospel, and true vital godliness and scriptural holiness.” The Christian Advocate printed matters of “miscellaneous interest” from the transcendent to the mundane: revival and missionary reports; doctrine; keeping the Sabbath; Sunday schools; dueling; temperance; general news; brief memoirs; poetry; book notices; items for children, youth, and ladies; history and natural science; and eventually commerce, agriculture, and the law.

The Advocate strove to maintain a “conservative-progressive spirit” that preserved “our blessed Theology unmarred,” while adapting to “changing circumstances.” In the same paper, you might read reports of a stirring revival in Ohio, catch up on Congress’s doings, and gain advice on how to wash your curtains. The Christian Advocate also published testimonials about the usefulness of reading Methodist literature—conveniently published by the Book Concern, of course.

The intellectual Methodist Magazine and Quarterly Review published more demanding (and longer) articles intended to “study the tactics of the opposing hosts, and throw up an impenetrable shield against all their fiery darts”: theological and practical memoirs, sermons, articles, and in-depth book reviews on matters of doctrine, church government, missions, and Sunday schools—with occasional attention to topics in science and history.

Combining preaching with publishing was in the blood of all Methodists: the African Methodist Episcopal Church began a distinct publishing arm in 1818, only two years after it officially wrested “Mother Bethel” from white control (see “My chains fell off,” p. 21). Its Christian Recorder, the first enduring periodical owned and edited by African Americans, began operations in 1848 and is still going strong today.

In the nineteenth century, the Recorder seldom counted more than 5,000 subscribers, but it exerted an influence well beyond these numbers, inviting contributions from all church members, including the “self-taught and the self-educated. . . . Come, clergy and laity, come friends, one and all . . . let us hear what you have to say” about establishing the “Redeemer’s kingdom upon the earth.” One writer commented that it acted as a “silent, but most efficient [African American] missionary,” going “where the colored preacher or teacher is seldom, if ever, heard of, much less, suffered to speak,” even entering the parlors of white “ladies and gentlemen.”

Other things besides periodicals accompanied Methodists as they conquered a continent. Memoirs of exemplary lives encouraged readers to aspire to similar devotional heights. Hymnals aided worship at camp meetings and church services, and during private devotions. Official Methodist hymnals stood in a line reaching back to John Wesley’s Collection of Psalms and Hymns (1737) from his unsuccessful trip to Georgia as a missionary. Numerous unofficial Methodist collections also encouraged devotional singing. The Wesleyan Psalmist; Or, Songs of Canaan (1842) was typical in offering, as its subtitle claimed, A Collection of Hymns and Tunes Designed to be Used at Camp-Meetings, and at Class and Prayer Meetings, and Other Occasions of Social Devotion.

No individual wrote more of the hymns in common circulation among these Methodists—and indeed among many evangelical Protestants—than blind Methodist poet Fanny Crosby (1820–1915). She gave the world over 8,000 published hymns including “Blessed Assurance,” “Pass Me Not, O Gentle Savior,” and “To God Be the Glory.” Often complying with requests to compose words to match melodies played for her, Crosby attested that she wrote her “most enduring hymns . . . during the long night watches, when the distractions of the day could not interfere with the rapid flow of thought.”

Crosby was not the only one bringing a Methodist message to the masses. The four Harper brothers, Methodists all, envisioned publishing as an evangelical calling and founded America’s most successful trade publishers for the general public, Harper and Brothers (now HarperCollins) in 1818 on a foundation of “character, and not capital.”

Instructive and moral literature

Although not restricting themselves to religious titles, the Harper brothers resolved to print only “interesting, instructive, and moral” literature. They competed aggressively in the national print market six days a week, but never allowed themselves or any of their employees to work on a Sunday.

Harper earned a national reputation as an innovator and leader and was the first American trade publisher to introduce book series: purchasers would buy a larger number of volumes, including lesser-known titles, if they thought the books belonged together. Harper’s Family Library offered families a wide assortment of biography, travel, and history selections.

They also published magazines. At midcentury, when only a handful of periodicals had subscription lists over 100,000, Harper’s Weekly averaged 120,000 subscribers. By 1885, 200,000 copies of Harper’s New Monthly circulated monthly in the United States and 35,000 in Britain. Its 144 two-column pages for $3 per year gave readers more words for the penny than any other monthly. And the most costly and elaborately illustrated volume in all of the United States before the Civil War was Harper’s Illuminated and New Pictorial Bible in 54 parts (assembled by the purchaser) with 1,600 engravings. The Bible—morocco-bound, hand-tooled, gold-embossed, and gilt-edged—sold for $22.50, a princely sum.

But Harper discovered its greatest publishing success of the century with a work that bridged religious and secular literature: General Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur (1880). By 1913 its sales skyrocketed to 2,500,000. Like Harper as a whole, it triumphed at the crossroads of Methodism and commerce, appealing to readers interested in detailed historical narrative, emotional plots, and doctrinal content. For many readers, its realistic story line reinforced biblical truth claims.

Even after a century, publishing still fueled Methodist growth and did for many what Nathan Bangs had claimed the Book Concern should attempt: “To guard the purity of the press, to promulgate sound, Scriptural doctrine, to spread the most useful information, and to proclaim to all within the hearing of its voice ‘the unsearchable riches of Christ.’” CH

By Candy Gunther Brown

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #114 in 2015]

Candy Gunther Brown is professor in the Department of Religious Studies at Indiana University–Bloomington and the author of The Word in the World: Evangelical Writing, Publishing, and Reading in America, 1789–1880.Next articles

The Damnation of Theron Ware

A Methodist pastor who falls prey to the world, the flesh, and the devil

Harold FredericDoing “more beyond”

Jennie Fowler Willing, like many nineteenth-century Methodist women, set out to change the church and the world

Priscilla Pope-LevisonPreachers, fighters, and crusaders

Here are the stories of some other Methodists who helped settle—and then transform—a continent

Gary Panetta and Kenneth Cain KinghornThe patriarch broods over his family’s future

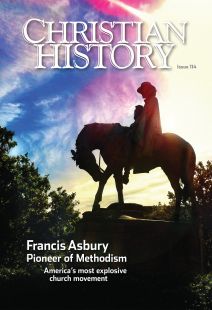

Asbury warned Methodists against settling down like other churches

Francis AsburySupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate