Service for peace

“WHAT'S THE MATTER, Burkholder? Why don’t you answer the judge?” the army major snapped at 22-year-old Paul Burkholder. Perched on a small chair, the young man sat in a semicircle of officers and lawyers sent to Fort Mead, Maryland, in 1918 to question those who refused to don uniforms as soldiers.

The major kept roughing Burkholder up, “until he got me in a position that I couldn’t scarcely talk [and] my voice trembled.” Finally the young man explained that he wasn’t afraid of fighting, but “if I have to take the uniform, I’m identified as one of the war-machine.” Citing “the Word of God,” he said, “When you accept the uniform, you’ve sworn your allegiance … to a military machine.” With only “a common school education,” facing an array of “learned men,” Burkholder remembered Jesus’ words (Luke 12:11) that “my Spirit shall reveal to you what you should say.” Later he reflected: “One thing I had when I left home, I had a congregation that was back of me, praying for me, and I also had a praying mother.”

Arguing for peace

Burkholder was one of several thousand World War I draftees in the United States and Canada who refused military service because of Christian peace convictions. Some conscientious objectors (COs) were mainline Protestants, believers in an optimistic theology that emphasized worldwide progress toward peace. Others (Jehovah’s Witnesses and some Plymouth Brethren) refused to fight due to their views on when Christ was coming back. A few nonreligious men refused service based on secular arguments for peace.

Order Christian History #121: Faith in the Foxholes in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Most COs, however, were members of the so-called historic peace churches: Burkholder’s Mennonite tradition, the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), the Church of the Brethren, and smaller related groups, such as the Amish and the Old German Baptists. These churches oppose violence, even in self-defense, and ground their stance in the teachings of Jesus, especially the Sermon on the Mount. For Mennonites, who trace their roots to the Reformation’s Anabaptist movement, and Brethren, who emerged from 1700s radical Pietism, nonresistance is an essential aspect of following Jesus in everyday life. Quakers tend to focus on the individual conscience and have a history of working with and within political systems; the Quaker saying “there is that of God in every person” led them to connect pacifism with broader issues of social reform.

Conscription of conscience

In the nineteenth century, authorities in the United States and Canada generally allowed COs to pay a sum of money to get out of the draft, or to hire a substitute. Although such arrangements strike us today as ethically dubious, they had a long tradition in Europe and were widely accepted by both pacifists and nonpacifists.

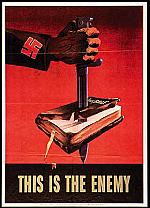

By the twentieth century, however, legal and religious ideas had changed. As Canada and the United States lurched toward “total war,” COs became highly unpopular—especially because some historic peace church members worshiped in German. Canada ended up excusing most COs in practice but subjected them to withering public criticism. In the United States, the government assumed—mistakenly—that all COs would accept noncombatant assignments within the military. They ordered draftees with religious scruples about fighting to report to military camps and await word on their status from the War Department.

Then the real troubles began. In some places COs were relegated to a corner of the camp in tedious, intolerable limbo and forgotten. But in other camps, if they so much as prepared their own meals, they were told they had voluntarily participated in the war effort and must now don a uniform. Those who refused to lift a finger risked court-martial for insubordination; dozens were convicted and sentenced to lengthy terms of hard labor, although virtually all of the verdicts were overturned after the war ended.

Camp commanders, saddled with responsibility for men whose beliefs they did not share and whose position the War Department refused to clarify, sometimes took their frustrations out on the COs. Objectors were beaten, denied medical treatment, and threatened with death. A few were even “baptized” in camp latrines in mockery of their beliefs. In the most dramatic case, four Hutterites (Jacob Wipf and the brothers Joseph, Michael, and David Hofer) were sent to Alcatraz and spent weeks hung by their wrists in unlit, underground cells. When that torture did not break their commitment, they were dispatched to Fort Leavenworth prison, where Joseph and Michael died. In a final insult, their bodies were shipped home in full military dress.

The pacifist Is the normal man

The experience of COs in World War I made no one happy. Army brass did not want the responsibility, and historic peace church leaders desired a plan for alternative service: direct, nonviolent contributions to society modeling a different type of Christian patriotism. In 1940 a novel experiment in church-state relations unfolded on both sides of the border. Known as Alternative Service Work (ASW) in Canada and Civilian Public Service (CPS) in the United States, the programs put COs to work performing “work of national importance” under civilian direction.

Participants lived in church-run work camps complete with barracks and mess halls. Governments provided facilities, while churches financed administration, food, health care, and small living stipends. Each camp was operated by a denomination (usually one of the historic peace churches) but open to participants from other churches. Eventually there were 151 CPS units across 34 states and 31 ASW camps in five provinces. George Baird wrote to a friend about his experience at a camp in New Hampshire: “They want to show that the Pacifist is the normal man, doing a normal job, receiving a normal wage, and living naturally and normally among people.”

About 12,000 men participated in CPS. The largest number, 40 percent, were Mennonites, followed by Brethren, Quakers, Methodists, smaller numbers from over 70 other Christian denominations, 60 Jewish participants, and members of the secular War Resisters League. In Canada Mennonites made up about 65 percent of the 10,000 men in ASW. Almost all Jehovah’s Witnesses, and some others, chose to go to prison instead. Quaker CO Harry Wright-Johnson recalled, “One of my friends was sent to prison for refusing to serve. Later my friend was pardoned by President Roosevelt.”

Work of national importance

Canadian COs helped build the Trans-Canada Highway, planted tens of thousands of seedlings on Vancouver Island, and maintained national parks. American participants worked for agencies like the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Land Reclamation, and the Public Health Service. A few volunteered to be medical guinea pigs for doctors’ experiments. Some, like Wright-Johnson, took on dangerous, glamorous assignments as “smoke jumpers” who parachuted into remote areas to battle forest fires.

Hundreds of COs in the United States and a small number in Canada worked in understaffed public psychiatric hospitals. They found conditions there unspeakable, sparking a postwar movement to reform mental health care. Although women were not liable for the draft, some expressed peace convictions by volunteering as nurses or dieticians in CPS or ASW camps.

CO camps were placed in rural, out-of-the-way places (like Lagro, Indiana, and Coshocton, Ohio) where they would attract little attention. Some COs wanted a more public witness, such as working with refugees in war zones. One US group trained to go to China, but Congress banned any COs from leaving the country. Some Canadians were allowed to go to Britain and care for children evacuated from London.

Like soldiers and sailors, COs served “for the duration,” but after the war, they were not eligible for their countries’ respective veterans’ benefits. In some cases churches developed systems of mutual aid to support men who had not received meaningful wages for years.

In 2002 Harry Wright-Johnson reflected on his war experience: “I think I could not have done anything but become a CO. I do not think it necessarily made me better. I think that is who I was.” He spoke for thousands who, like Burkholder decades before, had decided to step away from the war machine. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #121 Faith in the Foxholes. Read it in context here!

By Steven M. Nolt

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #121 in 2017]

Steven M. Nolt is senior scholar at the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, professor of history and Anabaptist studies at Elizabethtown College, and author of 14 books on Mennonite and Amish history.Next articles

Christian History timeline: World Wars

In the space of just over three decades, large portions of the world were plunged into life-changing conflict

Support us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate