Stubborn saint

WANG MINGDAO was one of the twentieth century’s most famous persecuted Chinese Christians. Born in 1900 during the Boxer Rebellion, a violent uprising against foreigners and Chinese Christians, Wang had an outstanding ministry as a pastor and evangelist, laboring as a contemporary of John Sung and Watchman Nee. Today’s Chinese house church movement had its beginnings in Wang’s resistance to governmental pressure.

But Wang’s ministry was shot through with paradoxes. He was a strong man who sometimes showed a troubling weak side. He was impeccably moral, yet resorted to lies when pressed. He stood heroically against evil and powerful political adversaries, but struggled deeply and sometimes failed catastrophically.

Born in conflict

Perhaps Wang was marked for trouble from the days of his birth during the Boxer Rebellion (see “Father, forgive them,” pp. 4–9). Wang’s father, a doctor at a Methodist hospital, feared the Boxers greatly. No one knows whether the elder Wang was a Christian, but the Boxers were set on killing foreigners and Christians, and he worked with both. At any rate, the death and destruction so disturbed him that he took his own life before his son was born. Consequently Wang grew up in poverty and suffered from frequent illness. Like his father, he would one day exhibit extreme fear in his own life and ministry.

Wang experienced a Christian conversion at the age of 14 while attending the London Missionary Society’s primary school; in those days Christian schools could operate openly in China. There an older student mentored him in the faith. Wang was first named Wang Tiezi, “Iron Wang,” but he later changed his name to Wang Mingdao, which means “to testify to the truth.” He had aimed for a career in politics, but soon set aside political aspirations in favor of the Christian ministry.

The making of Iron Wang

In Wang’s ministry many potent factors collided—powerful convictions, unalterable stubbornness, and perseverance in the face of politically motivated harassment. In the 1920s he founded a church called the Christian Tabernacle: independent and non-denominational, not depending on any foreign funds. In the face of Japanese imperialism, which troubled China beginning in the late 1930s, Wang established a reputation as a fearless preacher and prophet of God.

The Japanese occupied northern China from 1937 to 1945 and organized a Christian federation that every church was required to join. At meetings of the federation, members were required to bow to the Japanese emperor and submit to the orders of the military.

Wang refused to join, putting his life on the line. The federation tried to persuade Wang through threats and through promises that it would not close his church, but he would not join an organization that he thought included nonbelievers. As Wang stood nose-to-nose with the Japanese imperialists, he refused to compromise his principles, and they finally gave up trying to persuade him.

Part of Wang’s refusal to bend stemmed from Western fundamentalists’ influence on him. The modernist–fundamentalist controversy began in the United States when the writings of certain German theologians advocating a “higher criticism” of the Bible became popular. This method asked questions about the authorship and background of the Bible that did not assume the Bible’s truth anymore than the truth of any other ancient text.

Many missionaries going to China between the world wars were trained in this approach to the Bible, and Chinese intellectuals themselves learned it from training in Britain, Europe, and America. In opposition, fundamentalists defined and defended “fundamentals of the faith” that they understood to be taught by the Bible and the church. Modernism was, to them, a form of skepticism that cast a dark cloud over faith and the Bible. For their part modernists thought the higher critical approach to the Bible was scientific and that fundamentalists were superstitious, legalistic, and antirational.

Wang was fiercely loyal to orthodox faith as defined by the fundamentalists and never wavered. For Wang modernists were nonbelievers who adhered more to science and reason than to faith and revelation, and he feared that associating with them would imperil his faith.

Furthermore Wang believed that the Three-Self Church, China’s only officially tolerated Christian denomination, was full of these modernists. The Three-Self Church used a well-known model conceived and promoted by Western missionaries Henry Venn, Rufus Anderson, and John Nevius in the nineteenth century called the “three-self principles.” The three components were indigenous financial self-support, self-leadership (rather than Western leadership), and self-propagation. This method hoped to make the church self-sufficient so it could grow more quickly.

Even though he would not join the Three-Self Church, Wang also took issue with foreign missionaries’ involvement in the Chinese church. When the leaders of a Presbyterian school where Wang taught in 1919 proposed a school militia for defense, Wang sharply disagreed. Though he was merely a teacher at the time, he voiced his opinion that the missionary leaders should go home. Eventually Wang would have his way, beginning and growing the Christian Tabernacle with no foreign help whatsoever.

Bending iron

Though Wang stood strong against the Japanese and against foreign missionaries, his iron will soon faced another test. When Chinese Communists came to power in 1949, Wang figured he could reason with them because they were Chinese and spoke the same language. He was sadly mistaken.

The Chinese Communists stepped up their efforts to enforce the Three-Self Church model as a way to increase control. When Wang rejected their calls to join the state-sanctioned church, they held “accusation meetings” to wear him down. Public humiliation punctuated these relentless interrogations. Wang’s exemplary moral behavior could not be used against him by Communist interrogators, but the Communists condemned Wang as a reactionary and as one who harbored reactionaries. As the Communist leaders harassed Wang, fear and self-doubt consumed him. He became unstable and even suicidal.

In July 1954 the Communists brought new pressure on Chinese Christians to attend a national Christian conference as a way to unite the Chinese church. Despite his fear, Wang held his ground. “I won’t attend,” he said. “My thoughts and faith are very different from theirs. I won’t associate with them.”

He said later, “Let me solemnly declare: not only must we keep away from unbelievers and their organizations, [but] even when it comes to believers in Jesus, we can only unite in spirit and not in organization.” He saw Christianity as a purely spiritual force and felt strongly that the government had no right to interfere with faith or the church.

No conference for Wang

One day he was visited by a group of men called “the Old Men of Shanghai” (they were all over the age of 75, and Wang was still in his fifties) who were attending the national Christian conference and hoped he would join them. His wife turned them away saying, “You know what his temper is like. When he speaks, he never worries about saving face. If you see him and things become heated, you will be embarrassed.” The rumor later spread that “even Wang’s wife knows his temperament. You can see how hard it is to deal

with him.”

Soon the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) adopted the three-self principles for its own benefit in what was called the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM). Under the pretense of uniting the Chinese church and freeing it from Western control, the party instituted a new state-sponsored, state-controlled church. Wang saw that his small bit of religious freedom was quickly eroding.

The three-self principles had originally been intended to encourage Chinese Christians to operate independently of foreign control and grow more quickly. Wang believed the CCP was now using these principles to control the church. But Wang pointed out that Chinese Communism itself was an imported Western ideology, supported with funds from foreign entities (primarily Soviet).

Wang, though beaten down by the Communists before through the “accusation meetings,” now stood up for his convictions. The CCP knew of Wang’s stubbornness and personal integrity but still sought to win him over through constant pressure, disinformation (conducting more meetings to discredit him), and regular, persistent interrogation.

Finally, in August 1955, the CCP imprisoned him. In prison he suffered threats and intimidation as other inmates and guards filled his mind with gruesome stories of torture and execution. The interrogations led him to confess to crimes against the state that he had not committed and to promise to join the TSPM in exchange for release from prison in September 1956. He was discouraged with God and ashamed of his failure. Confused and distraught he fell apart emotionally.

Before prison Wang had underestimated the enormity of the challenge he faced. He became, as he later said, confident that he was strong and could stand up to any foe. When he recovered his emotional health, he realized that he had made a mistake. He would not join the TSPM. He told authorities that what he had confessed was a lie; he had not committed any crimes. Consequently he was rearrested and imprisoned in 1958. It would be a long road as he was not released until 1980. In 1963 he felt God restoring and reviving his spiritual life and remained faithful for the next 16 years of his sentence.

The government offered to release Wang from prison a few months after his rearrest in 1959, but Wang refused to leave, insisting that the government owed him an apology because it had imprisoned him as a criminal even though he had broken no laws.

The old Wang was back, defying unjust authority and stubbornly refusing to cooperate, even when it would have benefited him personally. His wife, Liu Jingwen, also imprisoned and released at the time of her husband’s first imprisonment in 1955, was rearrested with him in 1959 and received a 15-year sentence. She was released in 1974.

Birth of the house church

Wang’s biographer Stephen Wang wrote, “Like many elderly people Wang Mingdao became extremely stubborn in his old age!” But for Wang Mingdao, it had begun a long time before old age. Wang died of natural causes on July 28, 1991, at age 91, in Shanghai.

In his defiance against the TSPM, Wang set the stage for the later house church movement (HCM) in China. The HCM consisted of Christians who refused to join the TSPM and worshiped together in homes and other buildings, desiring to elude government control. Such gatherings were considered illegal and might at any time be interrupted by police who dispersed worshipers or took them to jail.

Ironically the house church movement was truly indigenous, fulfilling the vision of those missionaries who had originally conceived the three-self principles. The CCP opposed the house church movement because it could not control it. The movement sought to serve God, not the government.

Wang lived a fierce spiritual battle that almost engulfed and swallowed him. Except for the grace of God, his life would have ended in disaster and serious defeat. But instead it became an encouragement to others facing opposition for Christ’s sake. CH

By Roy Stults

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #109 in 2014]

Roy Stults is educational services coordinator at The Voice of the Martyrs-USA and writes on the history and theology of missions.Next articles

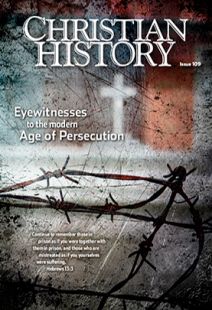

Editor's note: Modern persecution

What you will read in this issue is, in part, history that is still being written

Jennifer Woodruff TaitIs there a global war?

CH discusses modern persecution with John Allen Jr., the author of a new book, The Global War on Christians

John Allen Jr.Recommended resources

Learn more about the stories featured in this issue and put modern persecution of Christians into historical context with resources recommended by CH editorial staff and this issue’s contributors.

The editorsSearching for me with pistols and daggers

The first Christian arrested under Pakistan’s blasphemy law tells his story

Daniel ScotSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate