Watershed: Los Angeles 1949

IN 1997 BILLY GRAHAM was a year shy of his 80th birthday. He had lived an extraordinary life. In the previous half-century, he had grown from an obscure itinerant preacher into a national leader of the emerging evangelical movement and an international icon accustomed to golfing with presidents and dining with prime ministers. By many accounts he ranked as the most influential evangelist since George Whitefield in the eighteenth century. So on the eve of his 80th birthday, he agreed to the requests of many people and put it all together in a memoir, Just As I Am.

The task was not easy. With a life so long and so filled with travel and events and people, where would he start? How would he find a narrative line to pull it all together? He judged that the fulcrum of his career—and thus the fulcrum of the memoir—rested in chapter 9, which he called, significantly, “Watershed: Los Angeles 1949.”

That choice was sound, for the tactics Graham deployed in Los Angeles etched the template for virtually all his crusade meetings for the next six decades. Most of the components had appeared in Billy Sunday’s revivals before and after World War I and in less developed form in Graham’s own Charlotte campaign in 1947. But in Los Angeles the combination was more than the sum of the parts, not least because of the sheer size and complexity of the endeavor.

When Graham hopped off the train in Southern California in mid-September 1949, he was bursting with energy. When he boarded the train home eight weeks later, he had lost 20 pounds and struggled with exhaustion. Little wonder. He had preached 65 sermons to an aggregate audience of 350,000—maybe 400,000—souls jammed into a Ringling Brothers tent pitched near the city’s central shopping district. The meetings ran every night and Sunday afternoons from September 25 to November 20. Around 6,000 people either committed or recommitted their lives to Christ. Graham spoke to countless civic, school, and business groups, making three to four appearances a day. He gave dozens of interviews. He even schmoozed with Hollywood celebrities such as Cecil B. DeMille, Spencer Tracy, and Katharine Hepburn.

Committee work

The story of Graham’s “Watershed” started back in 1943. At that time, the Christian Businessmen’s Committee of Los Angeles joined with local parachurch organizations such as Navigators, Christian Endeavor, and, especially, Youth for Christ (YFC) to create the Christ for Greater Los Angeles committee. Between 1943 and 1949, the committee sponsored 17 citywide evangelistic meetings, led by nationally known revivalists such as Hyman Appleman, Jack Shuler, Merv Rosell, and Charles Templeton (who later lost his faith). Not satisfied, in 1948 they invited a relatively untested young preacher from North Carolina to try his hand.

The first time the committee invited Graham, he turned them down, thinking the time was not ripe. The following year they asked again, and he agreed—but with conditions. He required that they incorporate clergy into the committee, secure the support of local churches (more than 300 eventually joined), increase the size of the tent to accommodate 6,500 people, and beef up the advertising budget to the then unheard of sum of $25,000 (equivalent to $244,000 in 2013).

In Just As I Am, Graham characteristically insisted the revival’s success was entirely “God’s doing” (his emphasis). But he underestimated at least three streams of influence.

The first stream grew from the external political, social, and economic environment. On Friday, September 23, two days before the revival, President Harry Truman announced that the Soviet Union had exploded an atomic bomb. The United States was no longer the sole possessor of nuclear weapons. That turn of events felt even more ominous because the Soviets had embraced the deadly, aggressive, atheistic ideology of communism. The threat felt frightfully real.

Six days after the revival started, mainland China fell to Mao Zedong’s Red Army. Communists possessed both the determination and the ability, in Graham’s words, “to holster the whole world.” At home things looked just as grim. Recurrent economic downturns and the spiraling threat of juvenile delinquency rattled Americans’ self-confidence. Beyond those perils, wherever Graham looked on the American landscape—and he looked everywhere—he saw multiple additional threats: militarism, racism, materialism, and rampant sexual immorality.

The second stream of influence grew from the committee and Graham’s awareness that revivals had to be “worked up as well as prayed down.” The committee initiated concerts of prayer (that is, people praying at the same time of the day in multiple places) fully nine months before the revival started. It systematically enlisted the support of hundreds of local churches and laypeople from the Southern California region.

But the committee also “worked up” the revival by using advertising adeptly. It blanketed the region with flyers, posters, and banners. The materials heralded the coming “mammoth” tent, “6000 free seats,” “inspiring music,” “unprecedented demand,” “dynamic preaching,” and “America’s foremost evangelist.” Hyperbole took no vacation.

The third stream of influence grew from Graham’s own style. Besides having smashing good looks, he knew how to dress the part. He was outfitted in pastel suits, billowing kerchief, hand-painted ties, flamboyant argyle socks, and wide-brimmed hats. He was—as his own advance billing put it—“tall, slender, handsome, with a curly shock of blond hair, Graham looks like a collar ad, acts like a motion picture star, thinks like a psychology professor, talks like a North Carolinian and preaches like a combination of Billy Sunday and Dwight L. Moody. . . . He uses few illustrations, no sob stories, absolutely no deathbed stuff.”

Man with a message

But of course the main thing was not Graham’s looks or dress but his preaching, which served as the centerpiece of the revival. Few considered him eloquent, but no one doubted his effectiveness. The content of the sermons proved predictable, night after night. Years later one of Graham’s close associates would say, “If you have heard Billy 10 times, you probably have heard all of his sermons.” Truth was, if followers had heard one of Billy’s sermons, they had heard them all. Sooner or later every one of them circled around to the same text, John 3:16: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” In every sermon of every service for the rest of his life, Graham would say, he drove for a verdict.

The messages followed a predictable format. In Act I, Graham began with a litany of the international and national perils noted above—communism, economic depression, immorality, and crime—among others. Act II consisted of Graham relating those external threats to internal ones of meaninglessness, loneliness, addictions, backsliding, or never knowing God in the first place.

All of those maladies ultimately grew from a single source, and that was the sinful heart. Graham made clear that while sin was innate—what theologians called “original sin”—it manifested itself in sinful acts. Yet the good news was that cleansing from sin and new life in Christ were available for anyone, simply for the asking and taking. Believe that Christ died for your sins, Graham boomed, receive him into your hearts, and then carry forth lives of faith and holiness. In short, the external threats and the internal ones mirror one another. And the solution for both is the same: Christ.

If the content of Graham’s sermons proved predictable, so did the manner of delivery. Clenched fists pounded the lectern, pointed fingers stabbed the air, and crouched knees hurled the preacher forward and backward. Graham paced the platform relentlessly, aided by a newly acquired lapel microphone. By one account he paced two miles during every sermon. One reporter said he revealed “the coiled tension of a panther.” The words poured forth fast and loud. A stenographer clocked the torrent at 240 words a minute. The speed was intentional. Graham self-consciously adopted the rapid-fire delivery of successful radio newscasters like Walter Winchell and H. B. Kaltenborn.

And then there was the volume. Time magazine called him “trumpet-lunged.” In later years, when Graham’s preaching much more resembled an avuncular fireside chat, he admitted that in the beginning he preached very fast and very loud. Throughout, Graham clutched a large Bible, which he quoted rapidly, accurately, and frequently. In a Bible-steeped culture, that strategy—born of deep conviction that the Bible contains God’s authoritative answer to every problem—added authority. At the end of these sermons, hundreds of men and women, who were (by photographic evidence) overwhelmingly white and middle class, steadily streamed forward to yield their lives to Christ. But not at first.

Slow start

The success of the Los Angeles revival has obscured our vision of how hard it was won. Despite concerts of prayer, meticulous organization, multiple neighborhood committees, and vast and intense publicity, the revival got off to a slow start. Initially, the committee scheduled it to run three weeks, from Sunday, September 25 to Sunday, October 16. In those weeks the crowds ran a respectable 2,000 to 3,000 per night, but since the tent seated more than 6,000, ushers spread out the chairs to make the audience look more substantial.

The local press paid little attention to the meetings. The committee placed ads, and neighborhood churches slipped in notices in their usual spots on the newspaper’s church page, but otherwise the revival seemed destined to follow the path of most revivals: earnest support from the faithful for a few days, maybe a few weeks, but nothing to make the history books. Unseasonably cold weather did not help.

Toward the end of the third week, Graham, song leader Cliff Barrows, soloist George Beverly Shea, and the committee fell into consultation and prayer about whether the revival should continue past the scheduled closing date. Uncertain, they, like Gideon in the Old Testament, asked God for a palpable sign.

Their prayer yielded results. First, a spell of warm weather rolled in on October 16, the very day the revival had been scheduled to close. And then, on October 17, Stuart “Stew” Hamblen came to faith in an early morning meeting with Graham at the hotel where Graham and his wife, Ruth, were staying. Hamblen was a storied country performer, radio show host, and local celebrity. The following night he professed his faith publicly at the crusade. The next week Hamblen gave his testimony on his radio program. With this exposure, the crowds grew and the committee extended the crusade for two more weeks. Later, Hamblen would write the Hit Parade favorites “It Is No Secret (What God Can Do)” and “This Ole House” to herald his new birth.

Kissed by a media mogul

The improved weather and Hamblen’s well-publicized endorsement were powerfully reinforced early in the fourth week. One night, as Graham entered the tent, he found the scene swarming with reporters, flash bulbs popping, note pads open. Asked what was going on, one journalist told him, “You have been kissed by William Randolph Hearst.”

In the next few days, the Los Angeles Examiner and the Los Angeles Herald Express, both owned by the publishing tycoon, showcased stories about Graham. Soon the Associated Press, United Press, and International News Service ran accounts too. Time entered the picture on November 14. Time’s cousin publication, Life, with 25 million readers, ran its own piece on November 21. The Los Angeles Times (not a Hearst paper) compared Graham—a “silvery-tongued young evangelist”—with Billy Sunday, the premier traveling pulpiteer of the previous generation. Graham and the press had found each other. Over the years Graham gained vast publicity from the press, and the press gained a steady source of revenue from stories about the affable, photogenic, and loquacious evangelist.

Folded into this story was another one, not important in itself, but one that gained importance for what it revealed about how legends develop and the impact they hold. Hearst was not known to be deeply religious, much less evangelical. So how did he hear about Graham, why did he decide to promote him, and how did he communicate this to his editors?

The answers to these questions remain murky. As to how Hearst heard about the revival, one story held that one of his housekeepers had told him about it, another that the Holy Spirit had directed the housekeeper to phone Hearst, and still another that Hearst caught wind of the meetings and came in disguise with his mistress, Marion Davies. The most credible narrative is that the committee had worked hard behind the scenes, through intermediaries, to win Hearst’s attention.

In any event, the reason for Hearst’s interest was evident. The tycoon was fiercely pro-American and fiercely anticommunist. Less well known is that in some ways he was also progressive: a supporter of women’s rights and an opponent of monopolistic business trusts and long work days—anything that exploited ordinary people. Most important, perhaps, he strongly supported a well-ordered society.

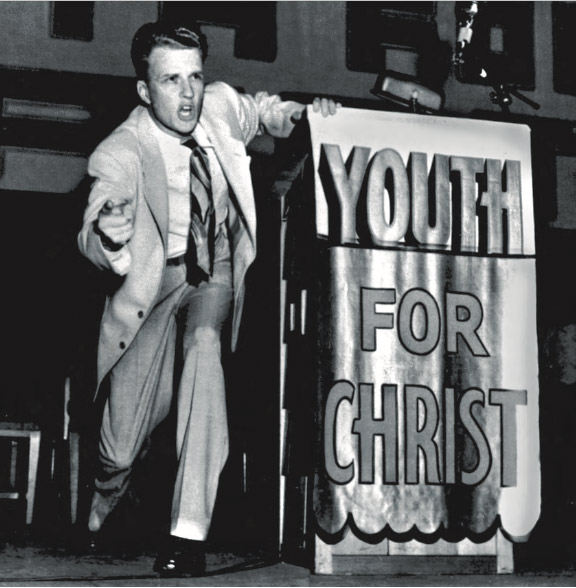

The need for a well-ordered society prompted Hearst to support YFC. The organization had emerged in the early 1940s, mainly in New York, Philadelphia, and especially Chicago. It aimed to provide “wholesome” entertainment, patriotic uplift, and evangelistic appeal to servicemen and women returned from military duty, as well as crowds of adolescents and young adults thronging city streets at night. Graham got his start in big city evangelism at a YFC rally at Orchestra Hall in Chicago, May 27, 1944, 10 days before D-Day. He stayed with YFC for about four years, gradually mixing YFC meetings with ones he organized on his own. By the 1949 Los Angeles meeting, Graham was entirely independent, but YFC had left its mark. His aggressive, flamboyant style and hard-hitting message had been forged on the anvil of YFC meetings in the United States and Europe.

Many people not notably religious, including President Truman and Hearst, liked YFC. Americans lived in perilous times, and YFC offered solutions. So it was not surprising that in 1946 Hearst sent a memo to his editors urging them to “Puff YFC” (CH emphasis). Stanley High’s 1956 biography, Billy Graham: The Personal Story of the Man, His Message, and His Mission, seems the first instance in which a serious biographer claimed that Hearst had sent his reporters a directive to “Puff Graham.” Most subsequent biographies, including well-researched books by William McLoughlin (1960) and John Pollock (1966), picked up the tale. (Graham himself uncritically repeated it in his 1997 memoir.) In 1983, however, Patricia Cornwell’s biography of Ruth Bell Graham cast serious doubt. No hard copy of the directive ever materialized, and Hearst’s son denied it, claiming that his father probably had said, “[G]ive attention to Billy Graham’s meetings.” William Martin’s exhaustively researched biography (1991) offered additional reasons to question the story’s veracity.

The “Puff Graham” tale not only amplified Hearst’s role in Graham’s rise, it also created an impression that Graham’s Los Angeles crusade owed its success to a random comment by a wealthy and powerful businessman who had a political and financial interest in the preacher’s work. It erroneously implied that the revival tumbled from the sky like a sacred meteor. Rather, the “Watershed Revival of 1949” grew from intersecting streams of historical influence already well in place.

Borrowed sermons, bigger tent

The committee extended the revival another week, and then another, and then one more, to a total of eight. Some people wanted it to go on indefinitely, but Graham had reached his limit. He had preached all the sermons he knew, started borrowing sermons from friends, and even replayed (with credit) Jonathan Edwards’s eighteenth-century fire-breathing masterpiece, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” The tent had been enlarged to seat 9,000, and additional thousands stood outside. One night, near the end, 15,000 reportedly jammed onto the grounds.

The revival’s energy drew also on additional celebrity conversions and the resulting publicity. Ranking at the top, perhaps, was the conversion of Louis Zamperini. An Olympic track star and decorated war hero (captured and tortured by the Japanese), his life had fallen apart after his return home. Facing divorce, alcoholism, and severe post-traumatic stress, he visited the tent sometime in the fifth week, found Christ, and spent the rest of his long life as a Christian inspirational speaker on forgiveness. He was slated to be Grand Marshall of the 2015 Tournament of Roses Parade when he died at age 97.

Why did the people come to the great tent in the first place? Graham was disarmingly candid. “People came to the meetings for all sorts of reasons,” he allowed. Some of them were religious. “No doubt some were simply curious to see what was going on. Others were skeptical and dropped by just to confirm their prejudices. Many were desperate over some crisis in their lives and hoped they might get a last chance to set things right.”

Whatever the reasons, thousands came to Christ for the first time. If the pattern in Los Angeles foreshadowed the pattern of later crusades—one well studied by historians and sociologists—a different reason proved equally important. Graham did not so much convert them to something wholly new, as call them back to something old. He touched their memories and reminded them of who they once were and who they now wished themselves to be, individually and collectively as a society. They, too, crossed a watershed. CH

By Grant Wacker

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #111 in 2014]

Grant Wacker is Gilbert T. Rowe Professor of Christian History at Duke Divinity School and author of America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation.Next articles

Billy Graham, Did you know?

Billy Graham’s political temptation, his friendships with entertainers and heads of state, and the impact of his music team

the editors“I would not call it show business”

Media made Billy Graham a celebrity; Graham worked hard to stay honest and authentic

Elesha CoffmanChristian History timeline: life and ministry of Billy Graham

A timeline of world events and the major events in the life of Billy Graham

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate