What did Luther know and when did he know it?

In 1545 the elderly Luther reluctantly authorized the publication of his collected Latin works. In its preface he told of his second course of lectures on the Psalms, given in 1519, a tense and dramatic year (see p. 17). Against its stormy backdrop, Luther approached the Psalms for the second time. But this time, he recalled, he was “armed” with a discovery that gave him a new understanding of the meaning of Scripture. (Luther’s casual comment to his friends in 1532 that the insight had occurred “on this cloaca [toilet]” has fascinated psychoanalysts and historians for years.)

For a long time, when Luther approached the letter to the Romans, he was held up by a single phrase: “the righteousness [or justice] of God” (Romans 1:17), “justitia dei”:

I hated this term “Justitia Dei” which by the common usage and custom of all the teachers I was taught to understand … [as] that formal or active justice … with which God is just, and punishes unjust sinners. For, however irreproachably I lived as a monk, I felt myself in the presence of God to be a sinner with a most unquiet conscience, nor could I trust that I had pleased him with my satisfaction. I did not love, nay, rather I hated this just God who punished sinners. … At last, God being merciful, as I meditated day and night on … “The just shall live by faith,” there I began to understand the justice of God as that by which the just lives by the gift of God, namely by faith. This straightway made me feel as though reborn, and as though I had entered through open gates into paradise itself. From then on, the whole face of Scripture appeared different.

But when did he discover this? The key insight he describes is actually found in his writings as early as his first Psalms lectures of 1513–1514. And medieval commentators consistently interpreted Romans 1:17 as referring to God’s “active righteousness” by which he makes us righteous, not to the justice by which God judges us. So Luther’s “common usage and custom of all the teachers” can’t be talking about biblical commentators on this bothersome passage. Rather, he must be speaking of more general philosophical and theological texts.

In short, if we take Luther’s “breakthrough” to refer exactly to what he described in the 1545 collected works—the understanding that God’s righteousness is God’s gift to us rather than the standard by which he judges us—then it must have come early in his life, because it is documented early in his writings. And it consisted not in a brand new idea but in a broader and more radical interpretation of an idea already known to the medieval tradition.

But if the breakthrough happened in 1519, it cannot have consisted simply of the insight that God’s righteousness is a gift. Luther already knew that by 1519. What shows up for the first time in 1519, in the middle of controversy with the powers of church and empire, is a clear account of “justification by faith alone”—a joyful confidence in God’s forgiveness through faith in Christ’s promise. Luther’s “breakthrough,” not confined to Romans 1:17, consisted of taking the idea of righteousness as gift and reorienting all of Scripture and hence all of Christian theology around it.

Why is this important? Those who insist on the “late breakthrough” in 1519 see Luther’s earlier teaching as inferior, still shackled by medieval Catholic ways of thinking. But if Luther was accurately remembering in 1545 that his key insight consisted of the realization that God’s righteousness is a gift, then he developed and intensified a theme already present throughout pre-Reformation tradition.

Against the persistent Christian tendency, found in all churches, to turn God into a demanding taskmaster who grades our performance in virtue and holiness, Luther insisted that the fundamental nature of God is shown in his generous gift of righteousness to those who do not possess it.

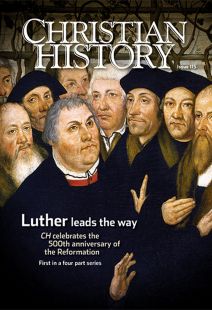

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Edwin Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #115 in 2015]

Edwin Woodruff Tait is a contributing editor to Christian History.Next articles

Luther Led the Way, Did You Know?

Luther loved to play the lute, once went on strike from his congregation, and hated to collect the rent

the editors and othersThe man who yielded to no one

Erasmus “laid the egg that Luther hatched,” many said; why aren’t we celebrating his 500th anniversary?

David C. FinkPreachers, popes, and princes

The men who mentored Luther, fought with him, and carried his reformation forward

David C. Steinmetz and Paul ThigpenChristian History Timeline: Luther Leads the Way

The century that changed the world

Ken Schurb and the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate